By Daisy Lu

Have you ever picked up a crime novel titled The Murder of Ms. Smith, and got the surprise of your life when Ms. Smith died? Have you ever been disappointed that the children’s book The Happy Adventures of Mister Crocodile did not contain any steamy, romantic scenes? It would be highly improbable that any of those situations actually happened to you.

Why?

Because there exist many conventions and structures within each genre. Although they might appear rigid or constraining, they are also needed to give a general sense of direction and familiarity to the readers, comforting them as they start a destabilizing new story.

However, just because someone likes the genre doesn’t necessarily means that they would love every single book in that section of the library. A well-written plot must surprise and move hearts, pushing the boundaries of its narrative style without ever breaking it. After all, even if a crime novel without a crime scene will certainly be shocking, the readers would still be disappointed and disoriented as their most basic expectation has not been met. In mystery novels, a crime needs to happen within the first few moments. A murder at the final chapter without any resolution would hardly classify for that genre, as the audience knowingly chose this book expecting a plot centered around the solving of the felony. The offer needs to correctly cater to the demand. If the readers wanted something else, they would’ve chosen something else.

As such, in science-fiction, a seemingly scientific concept is taken to the extreme of the author’s imagination, introducing new and futuristic environments. Extraterrestrials existences, outer-space explorations, and wild technologies transcending physical laws are common themes of this genre. The survival of humanity threatened by an alien race? Nothing too surprising here. After all, narrative frames are unavoidable. They serve as a structure holding up a concept, framing an idea just like a painting in the museum. Yet, what happens when the frame covers the whole picture? What happens when one becomes the victim of an overly convenient structure, for example, on a bad science fiction TV show?

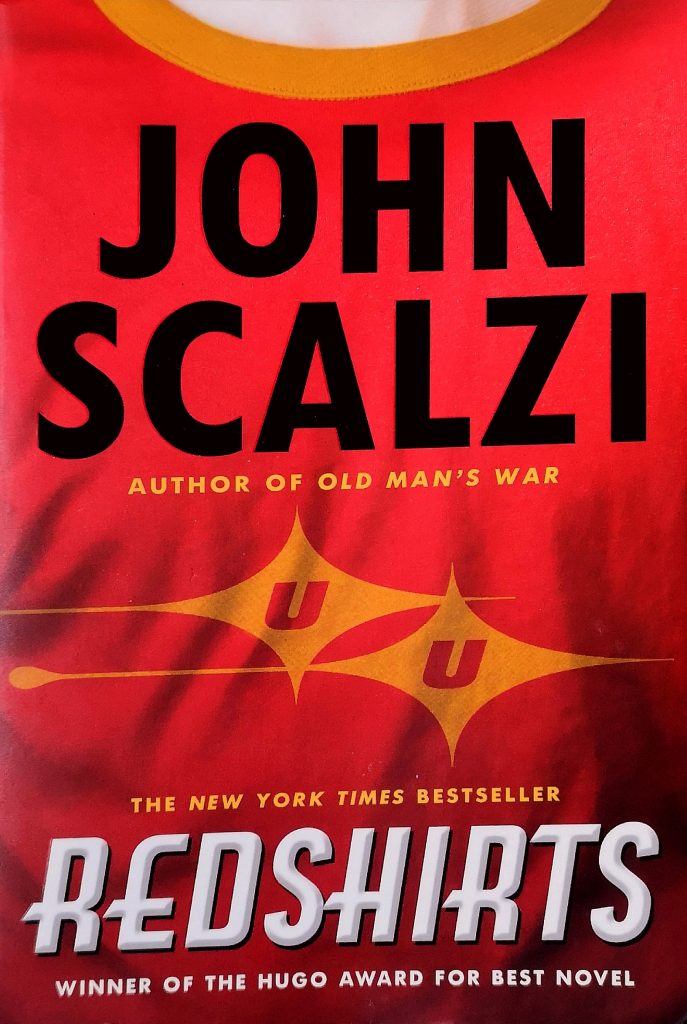

John Scalzi’s humorous novel with three codas, Redshirts, explores the limit of such plot-driven fiction. The protagonist, Andrew Dahl, is fighting for his life after he discovers that he is only a glorified extra on a bad television show, destined to die just to give an audience a thrill. As can be shown by the protagonist’s despair, Redshirts denounces the lazy writing that creates pointless deaths simply to prompt hollow, short-lived dramatic moment. By allowing Andrew Dahl, a simple supernumerary, to become the hero of his own story, John Scalzi’s work is promoting better in-depth characterization that can elicit stronger, more genuine emotions, as humans are complex beings capable of more feelings than a those of a disposable plastic soldier.

In the novel Redshirts, newly hired Dahl recognizes the suspicious behaviour of his fellow crewmen on the Intrepid, who all seem to work hard to avoid five specific senior officers. The latter appear to be the cause of suspiciously high rates of death among crew members who serve with them. Despite the substantial amount of critical mission failures and sustained injuries, Abernathy, Q’eeng, Kerensky, West and Hartnell never seem at risk of dying. Unable to explain these ridiculous statistics, the xenobiologist turns to Jenkins, a brilliant programmer who hides in the ship’s service tunnels, tracks the senior officers, and warns the crewmen of their whereabouts. Jenkins’ most rational explanation? All of them are fictional characters from a televised show that aired thousands of year ago and started in 2007. As glorified extras (minor characters with a backstory), Dahl and his comrades are destined to die in order to create more dramatic tension than the more common deaths of the extras, since the audience cares a little more about them. Refusing to leave their fate to external powers such as the Narrative and refusing to die purposelessly only to entertain an audience, the group decides to return to the past. Their goal? To convince the writer of the show to change this narrative. Their pursuit of a meaningful life, and – most importantly – death, shows the importance of control over one’s values and freedom, whose decisions should be unaffected by outside perspectives. In fact, Hester concludes that “ [a]fter everything, what it all means is that if one day we slip in the bathroom and crack our head on the toilet, our last thoughts can be a satisfied, ‘Well, I and only I did this to myself.’” His need to make his own mistakes infers that rather than aiming to avoid death, the characters wanted to take control over their own lives and be held accountable for their own actions. They are able to do so and “live happily ever after,” even after the end of the novel and even outside of the structure because, as human beings, they are capable of complex thoughts, desires, and feelings.

Because the characters’ development happen without the writers of the TV show realising it, Redshirts underlines the common issue of the lack of profound characterization in some science-fiction novels. Unexplained science statements may be skipped over, but that does not mean the explanation and reasoning behind the characters’ actions should be compromised. Compensating for the lazy writing of the The Chronicles of the Intrepid by filling scenes with deaths, explosions, and overly dramatic lines does not express the full potential of science-fiction that could and should aim for more than the mere sufficiency defined by the structure of this genre.

In Red Shirts, characters, in fact, do have more potential than that which the writer is giving them. Jenkins, who only appears for mere seconds to mourn the death of his wife on the show, continues to develop as a character to his full potential and has a major impact on the novel’s plot by discovering the most rational explanation for the staggering death statistics. His contribution to the mission (all prompted by his grief over his wife) ultimately leads to the freedom of the group. Humans form a complex social network with countless possible events initiating even more outcomes. The death of countless extras has had an incredible effect on Jenkins’ growth, creating impact unforeseen by the writers of the TV show.

A plot driven story can only scrape the surface of these limitless prospects as fate exceeds any form of attempted control; rather, these unexplored facets of the characters reveal tremendous potential for the plot, as can be seen by the contrast of contributions their growth offers to the storylines of Redshirts and The Chronicles. By exploring more dramatic tension from the characters, pointless and random deaths, such as being eaten by ice sharks, pornathic crabs, or land worms, could easily be avoided. The genre of science-fiction has incredible potential for more in-depth content that can have effective impacts. Reduced to its form and structure, this potential goes to waste.