Third part of a new series exploring comics history from the 1930s to the present by considering crucial works from each period. Whether a comic-shop virgin or an obsessive collector, you’re sure to learn something new and surprising!

As the 1960s and 70s rolled by, the pious certainties of the previous period fell away one by one. The illusion of safety was shattered, in part, by a few shots from a Dallas book depository in 1963, the infallibility of the US military by the disaster of Vietnam, and the incorruptibility of the government by Watergate and all the revelations that followed. Despite it all, the cult of scientific progress remained firmly in place—but it seemed increasingly pointless with all the institutions supporting it now being called into question. Questions, in fact, assaulted the American public from every direction in the eighties, many existential and paralyzing. It feels entirely appropriate, then, to take Denny O’Neil’s The Question #1 as representative of this era of superhero comics—and not just for the pun of it. This comic is relentless in its inquiry, toward its protagonist as well as the world he inhabits—a world which looks a great deal like the real one.

By 1987, the year the series debuted, comics had come a long way since the groundbreaking yet lighthearted days of the Silver Age. The humanism introduced by Lee and Kirby gradually came to dominate characterization, leading to steadily more dramatic—and subversive—plotlines. Spider-Man’s love interest Gwen Stacy perishes in a botched rescue attempt, the Teen Titans are devastatingly betrayed by one of their own, and Green Arrow discovers to his horror that his sidekick Speedy has become addicted to heroin. The last of these circumvented the draconian Comics Code that had been set up to police the industry in the wake of the fifties moral panic by using the loophole of presenting an ‘educational’ message. That it did… but it also hastened the Code’s overdue collapse, and with it, the end of the Silver Age of Comics.

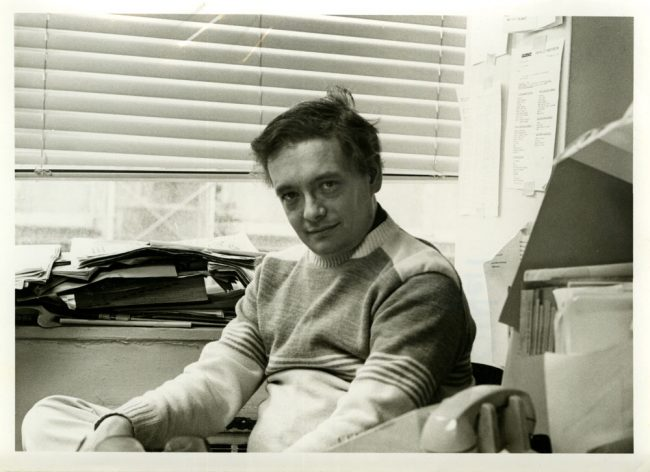

The man responsible for that seminal Green Arrow story might well be said to be the most influential of all Bronze Age writers. Denny O’Neil left his mark on Wonder Woman, Batman, and Green Lantern, updating all three for the gritty, paranoid present, before turning to the relatively obscure Question. Vic Sage, enigma-themed crimefighter, was created by Spider-Man co-creator Steve Ditko for DC’s rival Charlton Comics and imbued with Ditko’s unique interpretation of Ayn Rand’s Objectivist philosophy.

An individualist, manifestly anti-establishment crimefighter, Ditko’s Question sees every crime bust as an opportunity for a self-righteous philosophy lesson. What’s more—and quite unusual for the expressly ‘kid-friendly’ Silver Age—Vic Sage never hesitates to use evildoers’ own methods against them, hardly caring if they live or die (reminiscent of the brutal pulp-inspired heroes of the Golden Age). It was not hard for this combination to tip into fanaticism; no wonder the character inspired the sociopathic Rorschach in Alan Moore’s Watchmen, the book that arguably ‘ended’ the Bronze Age. O’Neil, however, had yet to have his last word on the period’s conventions and subject matter.

The Question we encounter in O’Neil’s series is a very different one—the blinding philosophical conviction of the original, reflecting Ditko’s own beliefs, is replaced by a profound spirit of inquiry. Bringing the character’s oft-forgotten secret identity as an investigative journalist to the fore, O’Neil made him a relentless examiner of society’s ills and hypocrisies. Every aspect of his life, including his crimefighting mission, is in doubt. This is an unapologetic portrait of a truly troubled man, going beyond O’Neil’s own conflicted take on Batman, who experiences spasms of self-consciousness but generally remains the inscrutable badass enemy of crime we all know and love. Vic’s debates with his mentor, Prof. Aristotle Rodor (the inventor of his characteristic blank skin mask), become more than a means to educate readers, like a philosophical variant on the classic ‘Flash Facts’ column; they serve as Socratic dialogues exploring the very nature of Vic’s soul, with the conclusion by no means foregone.

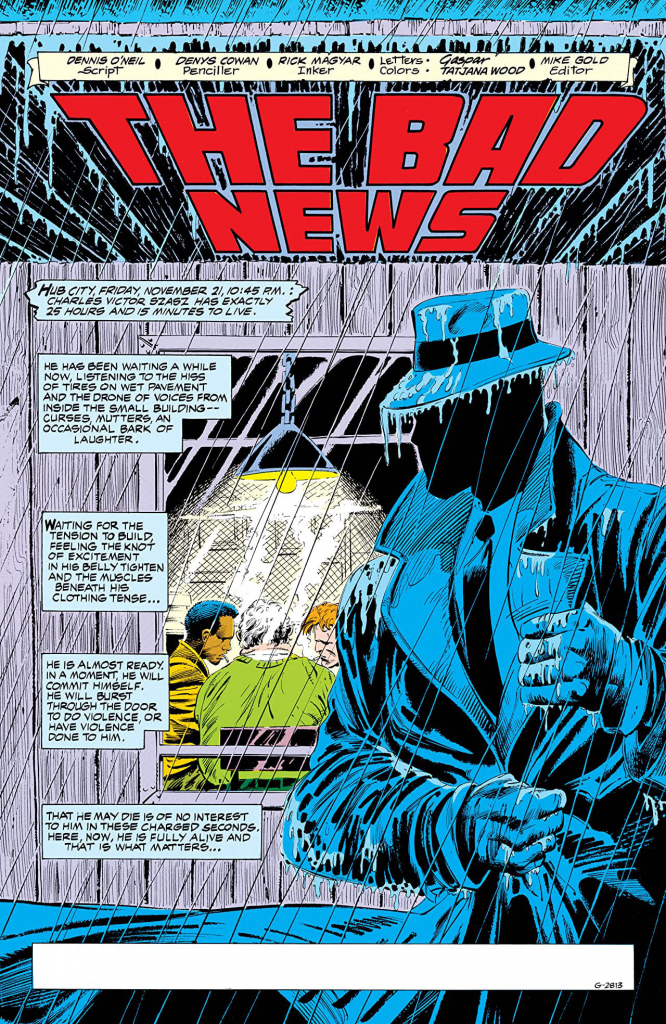

The issue itself announces its eighties-ness from the first page, from the splash panel with rain pouring down a dilapidated alleyway to the ominous captions arranged dynamically rather than fixed at the top of the panel (this was a time of great innovation for lettering, the most underappreciated craft in comics). Visually or writing-wise, no one could mistake this for a Silver Age comic. The disrespect of authority, the greatest of sins in the eyes of the Comics Code, is particularly blatant: Vic’s response to a policeman asking why he doesn’t join the force is, “THEY WOULDN’T LET ME. I PASSED THE IQ TEST.” To blindly accept what one is told is a mark of stupidity in this world, much like in paranoid post-Watergate America, a nation haunted by the harrowing costs of its past faith in the political system. In such a setting, the old gleefully pro-establishment superheroes seem more than irrelevant; they’re laughable. Anguished, violent Vic Sage might be the best we can hope for.

Yet even in demolishing what came before, O’Neil lays the foundations for an all-new vision of the superhero—as yet unrealized. The Question #1 hardly includes any traditional pulp superhero elements at all; instead of grandiose battles, plans for world domination, and exotic locations, the comic prefers to wade in the muck of inner-city crime and mundane corruption. Even the ninja assassin Lady Shiva hardly does anything except pull out some martial arts moves that immediately knock our hero to the ground. She then has her goons shoot him in the head and drop him in the water, where the narration declares him unambiguously dead. Obviously (spoiler!), this is not the case, but the symbolism is there: even such a basic fact as the hero’s survival can now be questioned.

The reader is left asking: how on Earth did we get here? Who can save us now? O’Neil leaves us on a monumental cliffhanger, awaiting the next phase of the superhero’s endless evolution—in which the archetype inevitably assumes cultural centrality once more, as it always seems to manage somehow (few subgenres have shown such sustained flexibility). And the hope was surely that it would re-emerge without losing the erudition—every Question issue included a recommended reading list—and grounded, multilayered writing that characterizes the best of the Bronze Age. That prophecy would prove both right and wrong…

Next time: postmodernism, Planetary, and the anti-superhero!