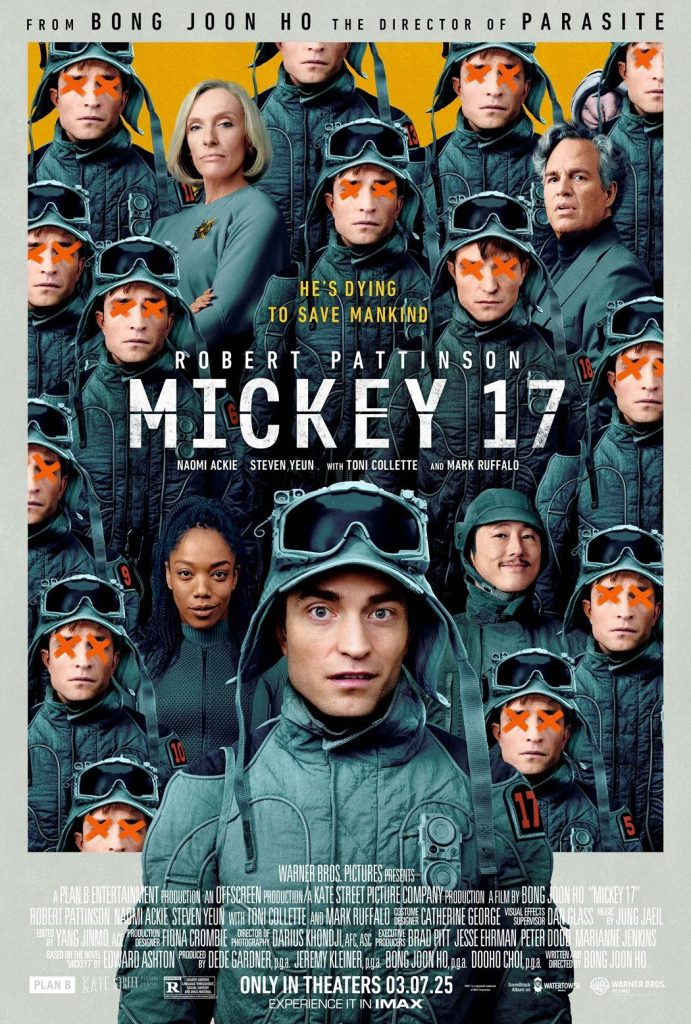

Mickey17

By Magdalena Nitchi

After the overwhelming success of Parasite, Bong Joon Ho has become a household name. His directorial style, rife with black comedy, sudden tonal shifts, and a focus on class inequality, has resulted in highly compelling work. His latest film, Mickey17, expands on these concepts in a science-fiction context.

The main character, Mickey (Robert Pattinson), is an impoverished young man who ends up aboard a spaceship set to colonize a new planet as an Expendable: a human whose entire body and memories have been scanned and preserved in a database. Thus, he is assigned the most dangerous jobs, and a new version of him is printed out when he dies. However, one day Mickey suddenly meets another version of himself, created when it was falsely assumed he had already perished. “Multiples” are expressly forbidden, and the Mickeys must keep their dual existence hidden to avoid their consciousness being erased forever.

Unfortunately, quite a few interesting plotlines in this movie are dropped or not entirely resolved, which is most disappointing when it comes to ethics. For a movie about cloning, Mickey17 is surprisingly sparse on commentary about it. It is also implied that Mickey is the only Expendable, but that angle’s not really explored.

On the other hand, the social commentary expressed through the character of failed senator Kenneth Marshall (Mark Ruffalo), the captain of Mickey’s ship, is purposefully heavy-handed but effective. The film’s absurdist nature, Marshall’s treatment of others as disposable, and Toni Colette’s excellent performance as a pseudo-republican housewife felt uncomfortably close to our current political reality.

Many of the actors played their roles superbly, though my favourite part of the movie was the dynamic between Mickey and his girlfriend Nasha (Naomi Ackle), whose slightly unhinged personality is a good match for Mickey’s pathetic nature.

This movie is weird. If you go in expecting a finished, coherent project, you’ll be disappointed. On the other hand, if you want a zany fever dream that may not offer resolutions but is compelling to watch and different from a lot of other recent Hollywood productions, this film is worth a shot.

The River Has Roots

By Catherine Hall

Like many others, I was—and still am—mesmerized by the masterful This is How You Lose the Time War, so I had high expectations for Amal El-Mohtar’s solo debut, The River Has Roots. To no one’s surprise, this novella is enchanting to the core and far exceeds expectations.

The River Has Roots is a retelling of a popular Scottish murder ballad, known as “The Two Sisters,” in which one sister drowns the other out of romantic jealousy. Just as she manipulates genre expectations in Time War, Mohtar cleverly subverts fairy tale conventions, transforming the ballad into a compelling tale of sisterly love.

Esther and Isabel are the youngest descendants of the well-known Hawthorn family, who tend to and harvest enchanted willows in the small town of Thistleford on the edge of Faerie. These trees are used mainly for spells and magic, which in this world is the study of grammar, while language in all its trickeries and complications forms the basis of magic. When a greedy human suitor separates the sisters on opposite sides of the border between Thistleford and Faerie, they must find their way back to each other through the power of love and song.

The strongest part of the novella is, without a doubt, the deep bond between Esther and Isabel. But Mohtar’s lyrical prose is the source of this novella’s magic, managing to be at once dark and whimsical. The only trouble with this tale is that it is too short, yet any additional pages may have broken the spell. As J.R.R. Tolkien once wrote, “Faërie cannot be caught in a net of words,” and Mohtar has wisely understood that the key to the enchantment is not to spell things out in too much detail—which is all the more interesting in a world where grammar and words are magic.

Brins d’éternité 63

Par Magdalena Nitchi

La revue Brins d’éternité demeure depuis plus d’une décennie un incontournable de ma bibliothèque. Le tome 63, paru en novembre 2024, est un véritable délice. Ces cinq nouvelles plongent le lecteur dans des univers totalement différents, en abordant des sujets comme le lien psychique entre un humain et son chien dans un futur semi-dystopique, une jeune femme qui monte dans un carrousel magique qui lui procure de beaux rêves chaque nuit, et un jeune lièvre anthropomorphe courageux qui remplit des formulaires gouvernementaux. Cette édition de Brins balance les réflexions sociales pressantes, le chagrin et des moments légers. La plume unique de chaque auteur mène à un recueil incroyable.

Mon histoire préférée est « Désintégration harmonieuse de la mémoire », un fascinant mystère de science-fiction. L’histoire suit Tom, un humain isolé dans un avant-poste chargé de surveiller la population de la planète AK210b. Exilés il y a des milliers d’années après avoir interagi avec l’IA d’une manière contraire aux lois de leur société galactique, les habitants d’« Akka » ont été abandonnés, changeant et évoluant en isolation. Cependant, lorsqu’une interaction inquiétante avec l’IA refait surface et un employé externe arrive pour vérifier le travail de Tom, de nombreux secrets cachés sont révélés. Anzala Peytoureau est un expert dans l’art de créer des tensions; il place soigneusement chaque élément du tableau final. Les rebondissements m’ont tenu en haleine du début à la fin.

Si les nouvelles constituent l’essentiel du magazine, j’ai aussi particulièrement apprécié les chroniques de ce tome. Célia Chalfoun et Marie Pelletier décrivent leur expérience avec le sous-genre cozy, qui est en plein essor dans tous les genres de la littérature de l’imaginaire. En tant que grande fan de ce sous-genre, je peux affirmer que leur enquête est idéale pour les lecteurs, autant novices qu’expérimentés, qui veulent trouver de nouvelles recommandations.

Si vous êtes amateur de nouvelles et de la scène littéraire SF/F québécoise, jetez un coup d’œil à n’importe quel numéro de Brins d’éternité pour une lecture vraiment divertissante.

The Raw Shark Texts

By Imogen Chambers

If you are reading this, I’m not around anymore. Take the phone and speed dial 1. Tell the woman who answers that you are Eric Sanderson. The woman is Dr. Randle. She’ll understand what has happened…

Ask yourself this: if you were to wake one day with no memory of who or where you are, what would you fear the most? What would—or could—you conceive to be the cause of your fugue? I may be wrong, but I don’t think your first guess would be a conceptual shark. And yet this is the exact dilemma our protagonist, Eric Sanderson, faces. Caught in a cycle of half-lives, Eric must piece together his past and attempt to contain the force that hunts him, threatening to consume his memories whole, and with them, his life.

Steven Hall’s 2007 debut novel, The Raw Shark Texts, is yet another example of the power of metafiction. Not only does the narrative make for a fabulous and gripping read, but the physical book is also an immersive art form, brimming with calligrams and codes. At the same time, the novel is more literary than I expected, being both eloquently written and discussing the metaphysical through the lens of language. As a great enjoyer of wordplay, I can also not neglect to mention how its title puns on “Rorschach Tests”. And so, as Hall explores the mind, language, and the significance of memory, he also brings to the fore his conception of the liminal—the so-called un-space, to which the book itself belongs.

The Raw Shark Texts is a uniquely compelling mediation on grief and paranoia that delves into the strange and speculative. But it is also a story of love and hope—one that is perfect for fans of the uncanny and psychological. In all ergodic fiction, the reading process is metaphysical, and this case is no exception. As The First Eric Sanderson claims, fiction is “a labyrinth… which can trap an unwary fish for a great deal of time.” And speaking of labyrinths, for those die-hard fans still suffering from House of Leaves withdrawal—myself included—Hall’s debut is certainly a worthy successor in the ergodic canon.

Jaws can take the backseat on this one—the metalodon is one of the most brilliant and imaginative ‘antagonists’ that I’ve come across in a long time.