By Ila Ghoshal

“The end justifies the means. But what if there never is an end? All we have is means.” In our attempts to imagine a world free from war, sickness or racial injustice, how much do we really think about the collateral damage creating a society where these are no longer issues would cause? Is it possible to create a utopia for everyone without there being hidden consequences or without requiring that many people make a large sacrifice? And if we try to think of a realistic means to achieve one of these ends, is it inevitable that many people would end up getting hurt for the benefit of others thus meaning that “we” are ultimately no better off?

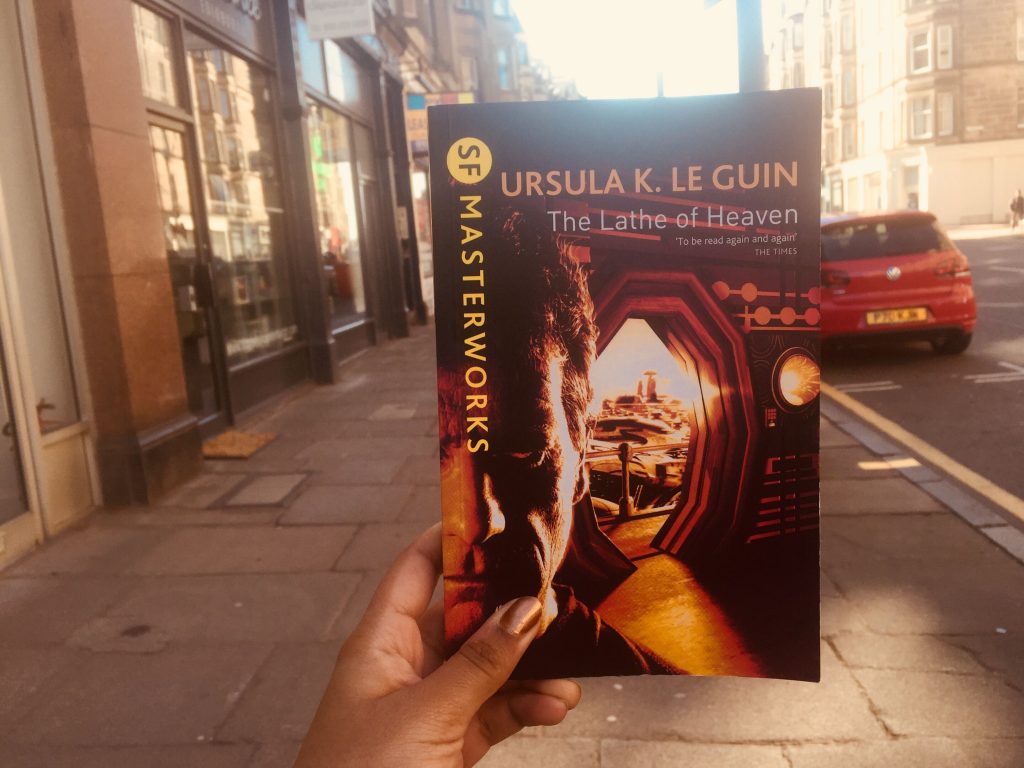

All of these ideas and more are explored in Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Lathe of Heaven. This novel, first serialized in the magazine Amazing Stories, is an exploration of sleep and dreams, namely dreams about creating a perfect world. It would go on to be nominated for the Hugo and Nebula awards, in addition to winning the Locus award.

Trying to create a utopia, given that it’s impossible to control its exact parameters, is a dangerous game as Dr. William Haber fails to learn in The Lathe of Heaven. When George Orr gets caught using his friends Pharmacy Cards to get extra drugs, he gets sent to Dr. Haber’s office for treatment. He tells Dr Haber that the drugs are to prevent himself from having reality altering dreams, a claim that Haber initially does not believe. However, once Haber realizes that George is telling the truth, he quickly starts using this ability for his personal gain and soon after to “fix” everything he believes is wrong in the world. Since Haber can only do this by hypnotizing George and instructing him what to dream, none of these suggestions work as he intends them to: a dream about not feeling crowded anymore leads to a plague that wipes out 6 billion people, a dream about word peace results in an alien invasion. George and Heather Lelache, a lawyer he hires to prove that what Haber is doing with his ability is unethical, attempt to stop Haber from continuing to alter reality as he sees fit; however, they do not succeed. Haber only stops when he gives himself the ability to dream as George does, which quickly drives him insane.

The concept of a perfect place has long been regarded as an impossibility. In fact, the word utopia itself is a play on the Greek homophones for “no place” and “good place”. And, when the human subconscious comes up with the solution to solving some of the world’s most complicated problems, people’s inherent pessimism, as well as the sheer number of variables in play, can lead to unintended consequences. For example, the scenario of peace between all countries on Earth is so complex, an alien invasion is more plausible to many people than peace having been reached without any external motivation. The malleable nature of reality in this novel allows us to explore the various ways in which a utopia can be constructed, as well as the practical challenges of creating such a reality. The most obvious solutions tend to create a utilitarian dilemma in which many people must suffer for the good of others, which begs for the question of whether living in a “perfect” world is something that should ever be sought. Le Guin shows that attempting to carve out a perfect world would still only result in a world that is perfect for a small number of people.

Although Haber is very optimistic about the potential of George’s dreams, George himself does not believe that he should not be interfering in reality since he has realized that he can never control exactly what happens because of the large number of variables at play. His beliefs reflect a balance between yin and yang, in sharp contrast to Haber’s aggressive and unwavering optimism. The principles of Taoism hold an important place in this novel, Taoist quotes often feature at the beginning of chapters and the title itself is a mis-translation of a quote from a Taoist sage. In fact, the title is a reflection of George’s view of himself as tool that can shape reality in the same way that a lathe is used to shape everything it touches, be it wood or metal. George sees himself as a tool, his ability used to shape reality into what someone else imagines to be an ideal world.

George’s beliefs and behaviour also reflect an unexpected of amount of strength: he refuses to use his ability to his own advantage and simply desires to be rid of them. George’s perspective on not interfering with what he sees as the natural order of things might seem to suggest a kind of spinelessness, especially in contrast to Haber’s loud, pushy and more assertive nature; however, ultimately, it becomes apparent that George is strong one. Haber’s quick descent into insanity once he’s acquired George’s ability shows us that our assumptions about strength may be mistaken and that adaptability and flexibility require more moral strength than trying to force things to conform to our view of how they should be. This novel shows that seeking to maintain balance is important and shouldn’t be regarded as inferior to traditional Western displays of strength especially when dealing with things as sensitive and subjective as dreams. In this way, the author shows how a worldview that lacks balance can quickly change a utopia into a dystopia.

All in all, The Lathe of Heaven is a very enjoyable book which explores the topic of dreams from a very interesting perspective. Le Guin’s writing style makes this book a pleasant read despite the relatively complex subject matter. Exploring the different iterations of “improved reality” was very interesting because it allows us to see the differences between what humans might wish from an ideal world and how they would go about implementing it. Furthermore, although the characters might each seem to embody very specific ideas without much nuance for the plot of the story to work, I enjoyed how the author developed the relationships between the characters. On one hand, George represents a very ordinary man who refuses to force things which gives him a kind of stability and strength. On the other, Haber’s ambition and desire to be a hero leads to his lack of any real personality other than how he wants to be seen. The juxtaposition of Haber’s and George’s personalities, as well as their strange relationship is interesting to see developed and the romance between Heather and George is touching. I would recommend this book to anyone who enjoys Le Guin’s other works or who finds the topics of utopia and dreaming interesting.

Revision : Alina Orza