Dune: Part Two is already the year’s highest-grossing release so far. Something about it has drawn audiences in despite the famously esoteric nature of the book it is based on. I’m not quite sure what that something is. The movie is enjoyable, visually breathtaking, and about as faithful to its source material as one can hope for, but several flaws hold it back from being this decade’s answer to the giant SF hits of yesteryear.

This sequel to 2021’s Dune: Part One adapts the second half of Frank Herbert’s novel. With his ducal house annihilated and his father killed by the rival Harkonnen family, Paul Atreides (Timothee Chalamet) and his mother Lady Jessica (Rebecca Ferguson) are left to wander the planet Arrakis, which is full of colossal sandworms and a mind-altering crop called spice that’s essential for space travel. Paul’s only hope of surviving Arrakis’ unforgiving desert and avenging his father is to forge an alliance with the indigenous Fremen. He positions himself as the fulfillment of their religious prophecy, the messiah who will lead them to victory against their Harkonnen oppressors.

As the plot meanders across Arrakis and other locations throughout the galaxy, we’re treated to stunning visuals, as expected: imposing brutalist architecture, sweeping shots of the desert, and a setpiece at the halfway mark that is intriguingly shot in blank and white. There’s a real visual style here, so welcome in our era of anonymous franchises, which highlights how the world of Dune is different from our own: starker, older, harsher.

But for the most part these images are all static, to the point that the first half of the film makes you wonder if the most exciting action you’re going to see on this cinema outing is the trailer for the new Godzilla x Kong. Although the movie hinges on Paul’s reluctant obligation to feed into the prophecy, it fails to build up any sense of suspense or doom. The sandworms—the most iconic part of Herbert’s worldbuilding—are underused. They’re basically depicted as clouds of sand, even in what should be exhilarating scenes where characters ride them. Still, if the first half feels as dry as its desert setting, the last hour is worth sticking around for, because the action and gorgeous staging are everything a space opera fan could hope for.

Part Two’s convoluted plot melding political intrigue, romance, and a galactic setting in a big spice melange needs a strong lead to sell it. Unfortunately, Chalamet is not at his best here. As a leader assertive enough to earn the respect of the warlike Fremen, he’s thoroughly unconvincing; he’s so much better suited to acting boyishly charming or looking tortured (the Gom Jabbar scene of the first film is not equalled by anything here). The film doesn’t give him much opportunity to do either of these things, preferring to show him swooning over Zendaya or barking lines at the Fremen instead. It’s lucky that Paul has the Voice at his disposal because I can’t imagine anyone taking his orders seriously otherwise.

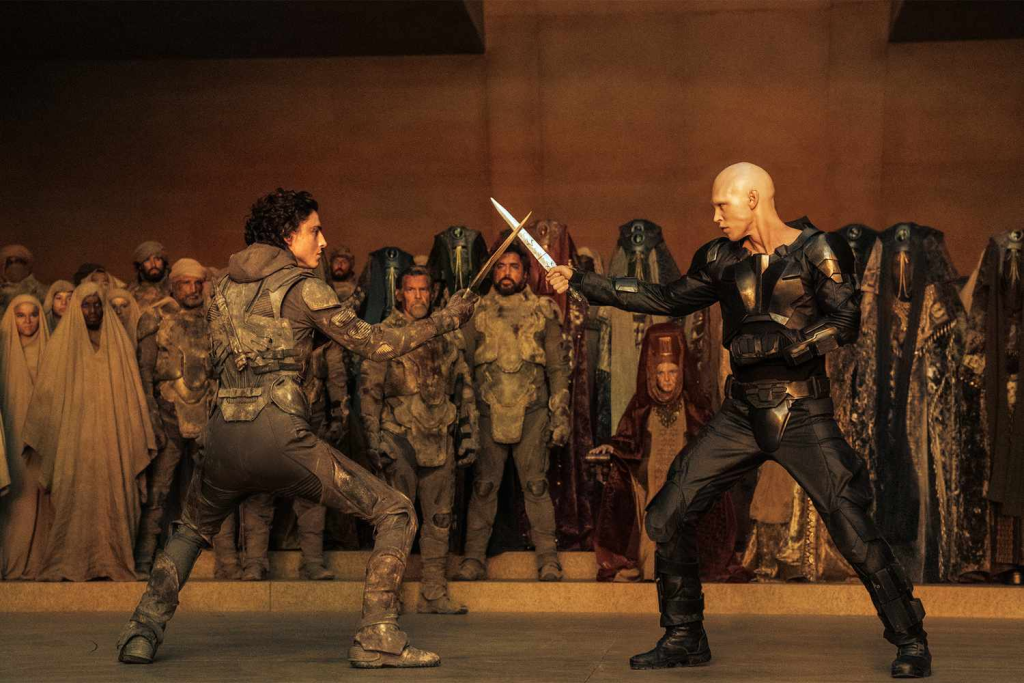

The rest of the cast gives much stronger performances. Florence Pugh brings gravitas to the few scenes she appears in, Javier Bardem is effortlessly funny as Stilgar, and Zendaya makes Chani’s emotional journey believable with her eloquent frowns alone. The surprise standout is Austin Butler, who clearly has fun with his over-the-top and borderline animalistic portrayal of the Harkonnen heir Feyd-Rautha.

The first film’s clunky writing is also back in Part Two. A fair amount of exposition is expected in an adaptation of a novel so dense that putting it to screen was long considered impossible, but the script’s inattention to character is less easy to forgive. Paul’s transformation into a ruthless antihero doesn’t happen offscreen—thank goodness—but it’s still far too abrupt. All his qualms about war and leadership seem to disappear over the course of a single scene, and not even in reaction to some Harkonnen atrocity. The novel has thoughtful things to say about charismatic leaders, chiefly that they’re dangerous even when they’re well-intentioned. Here, the moral seems to be “don’t drink the blue Gatorade” instead.

Despite its faults, the script does offer some welcome departures from the book, like the fact that a sizeable group of Fremen, including Chani, do not believe in the prophecy at all. Besides creating dramatic tension for Paul and Chani’s relationship as his religious stature grows, this change pushes back somewhat against the book’s uniform portrayal of the Fremen. Paul’s rise to power is made more compelling because he must earn the more skeptical northerners’ trust first, after which it’s much easier to believe that he can convince the “fundamentalist” southern tribes to follow him. As a result, there’s also more focus on the populist aspects of Paul’s ascent, which lessens the temptation to pin it on Fremen subservience alone. It’s the kind of improvement on the source material that a good adaptation has the power to make, but it’s held back by its clumsy execution. Though the entire Fremen culture has clear Arab inspirations, the religious fanatics of the south are the ones who look most like stereotypical turban-wearing bearded men, explicitly distinguished from the northerners by their non-American accents.

In its portrayal of the southerners’ faith in Paul, the film sometimes veers into mockery, undermining its own narrative. The introduction of the northerner agnostics exacerbates the issue. If there are people who can see through Lady Jessica’s missionary propaganda, it becomes harder to sympathize with those who do accept Paul as a messiah, and easier to overlook their reasons for doing so: faith, sure, but also intimidation, their bleak situation, and a history of colonial oppression. Besides the fact that the southerners are not actually that gullible—in the end, they’re right that Paul is the fulfillment of their prophecy, and the Bene Gesserit’s, too—portraying them as overeager with their faith makes all that time Paul spent earning trust from the skeptics a lot less important.

Dune: Part Two is overall a serviceable movie, succumbing to the issues of bloat which plague many blockbusters, but also wrangling source material that is dense and challenging. Fans of Herbert’s can finally rest easy now that the story has been given a definitive movie adaptation, though the film has not been so eager to please the Dune buffs that it hasn’t taken some interesting risks with the source material. Even casual moviegoers will be impressed enough with the film’s rich world to look forward to the probable next installment in a few years. There’s a lot to like and a few things to criticize, but the biggest flaw isn’t one I can put my finger on— just some failure to gel that left me thinking, “Was that it?” even after two and a half hours.