I have often been accused of being a ‘hater’ regarding movies. While there might be some truth to that, I’d like to say in my defence that I like a great many things—but sometimes it’s just more fun to take the piss out of a film that really deserves it. I say this as a preface to yet another review that skews to the negative because, I swear, I wanted to like Late Night with Devil! Sadly, though, the film had other plans. By hitting us over the head with exposition we could have figured out ourselves, it completely undermines its own scares and suspense… the same fatal flaw that’s weakened horror movies ranging from Dark City to Nope. But before we get into my thoughts on that broader trend, a brief plot summary of Late Night is probably in order.

The film takes place circa 1977 in an L.A. recording studio over the course of a single night—but not just any night. It’s sweeps, the annual period when networks calculate their advertising valuation, which just so happened to overlap with Halloween that year. Jack Delroy, host of the fictional Night Owls on the equally fictional UBC network, hopes to pull a ratings coup and save his failing show by inviting supposedly supernatural guests. Naturally, he gets much more than he bargained for, but you guessed that already, didn’t you?

Starting with the good: Late Night with the Devil is visually incredible (except for that awful AI art), recreating a Johnny Carson-esque ‘70s late-night show down to the minutest details. Even the resolution and aspect ratio look gorgeously vintage, unlike all those recent nostalgia throwbacks that can’t help but film everything in HD (like David Fincher’s Mank, which made such a big deal of its ‘40s aesthetics). It makes it all the more effective when the movie breaks that mould for dramatic effect later on—though I won’t tell you why. Suffice it to say that Late Night manages to convince you you’re watching a lost episode of a fictional late ‘70s Late Show clone for most of its runtime, which is no mean feat.

In this context, the fairly pedestrian scares on offer become far more effective. By placing what is essentially yet another Exorcist riff in the middle of cheesy scripted banter and amusingly phony psychics, the filmmakers keep us from seeing the overused tropes for what they are. In fact, they almost succeed in investing them with the inexplicable terror they would possess if we witnessed them in real life. It’s a rare case of found footage done well. The whole production also benefits significantly from an extremely committed cast of mostly unknowns, led by character actor par excellence David Dastmalchian, who delivers a simultaneously sympathetic and sleazy performance.

The film’s failure really comes down to a single flaw, which makes it all the more disappointing: the opening. Not coincidentally, this is one of the few parts of the film that deviate from the fictional telecast. But the greatest sin of this sequence is that it lays everything out far too neatly. Some of the best and scariest ‘found texts’ in fiction derive their horror from the mystery of their origins. The Blair Witch Project, for example, tells us just enough to whet our appetites, then lets the footage do the rest. House of Leaves frames its central text with an even more contradictory and inexplicable commentary. By contrast, Late Night with the Devil, apparently lacking confidence in its ability to make the footage it shows us interesting on its own terms, starts off with an expository montage that lays out Jack’s entire backstory and even the secret key to his success… which the film later treats as a shocking reveal.

Oddly enough, the film actually does a great job of subtly alluding to said backstory before the hints pay off—but these hints end up being totally unnecessary since we already know everything and can easily guess where it’s all heading. And, though it’s all admittedly done with great aplomb, everything still unfolds pretty much as you’d expect if you’ve ever seen any supernatural horror movie. It’s the clearest case of an ill-advised editing decision spoiling a whole movie that I can think of. But that doesn’t mean it’s the only one—this particular malaise has sadly plagued horror, a genre that’s at its best at its most cryptic, ever since Hitchcock ended Psycho with that infamous psychiatric explainer.

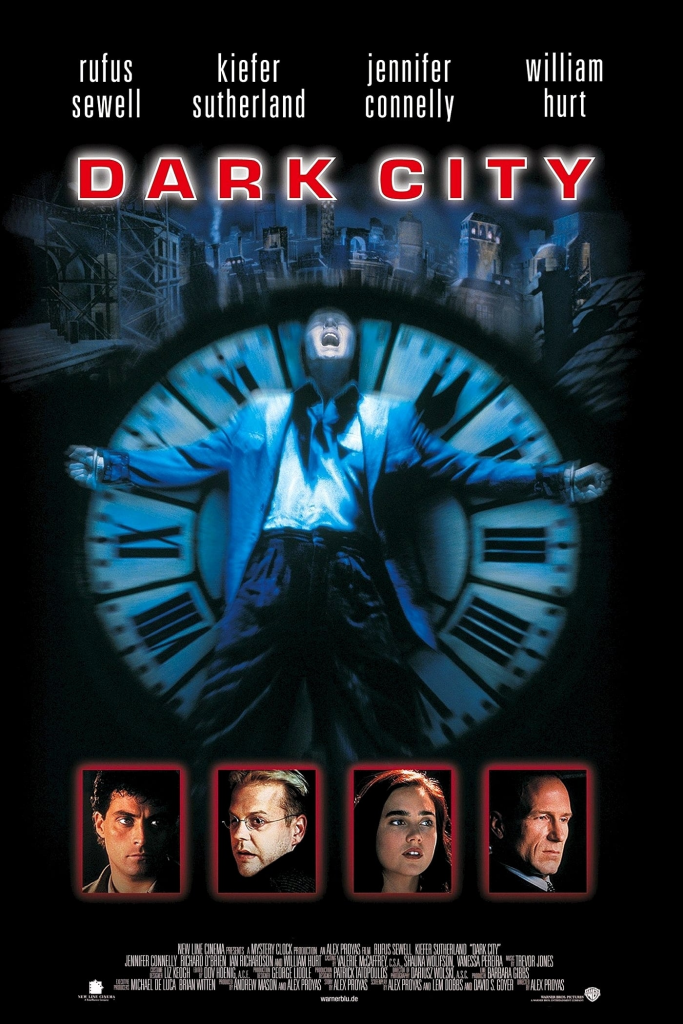

Even modern classics are not immune to this curse. Seminal ‘90s SF horror Dark City was also first released with a prologue that gives away its biggest twist. The Director’s Cut remedies this, but I can’t help but feel that the unfortunate attempt at audience coddling hampered the film’s underwhelming box office take at the time. But did the studios learn? Take a wild guess. Instead of embracing intriguing mystery, it’s become increasingly common for media within and outside the horror genre to play it ‘safe’ by relentlessly over-explaining.

Trailers have always and continue to do this, of course, but at least those can be avoided with enough dedication. The practice of defanging any surprise and ambiguity within the film itself is far more worrying as far as I’m concerned. It’s as if creatives—and the companies behind them—don’t trust audiences to handle works that don’t make it perfectly clear from the start exactly what’s going on. Sometimes, the effect is minor: Nope would have been even better if the nature of the UFO hadn’t been so thoroughly dissected, but it’s still a great thriller. For already-middling films, though, the effect is devastating—the blatant telegraphing of the eventual twist killed the little drama Don’t Worry Darling managed to generate. It’s enough to make one long for the heyday of M. Night Shyamalan.

Perhaps, like Dark City, Late Night with the Devil will eventually get a recut that better preserves some of the enigmatic quality it aims to conjure. But for now, it’s yet another casualty of an industry that persists in seeing fiction as content that should be as predictable and un-challenging as possible. That’s not how you get the next Don’t Look Now, The Shining, or Get Out. To its credit, Late Night does plenty that merits discussing in the same breath as these classics. It’s just not enough to make up for the fundamental meekness at its core.