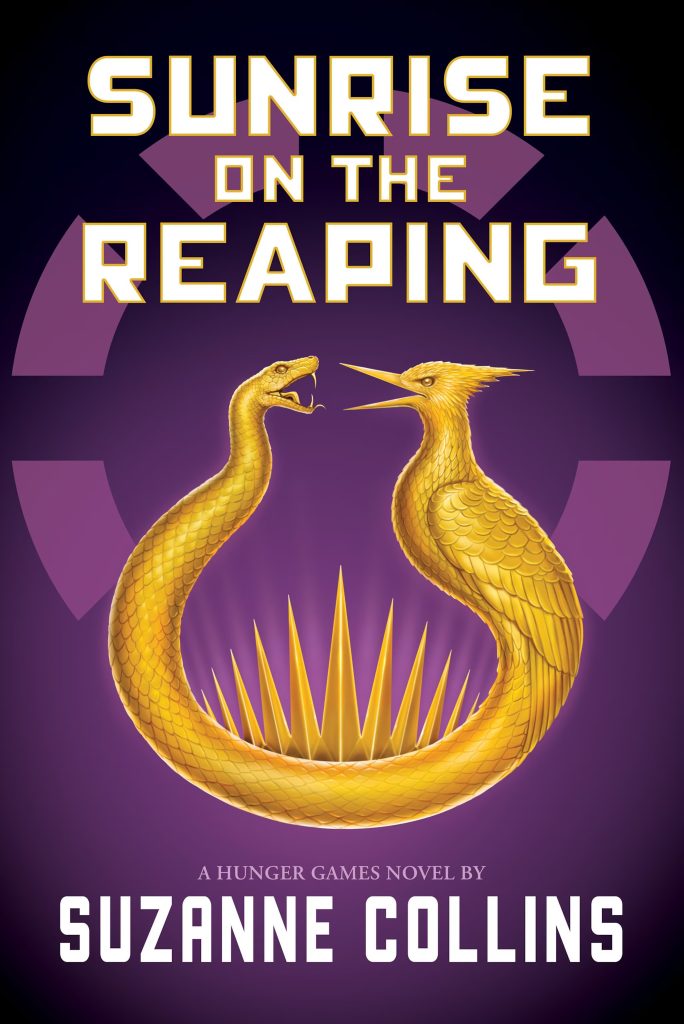

The Hunger Games trilogy made author Suzanne Collins a household name in 2010s YA literature. Now, the series has once again skyrocketed in relevance thanks to the publication of The Ballad of Songbirds and Snakes in 2020 and its latest prequel, Sunrise on the Reaping. If you are at all literarily inclined, it has been virtually impossible to ignore the purple and gold cover, which has been omnipresent all over social media. Countless bookstores have repeatedly sold out of Sunrise since its release in mid-March. The staggering 1.5 million dollars it garnered within the first week of its release has far surpassed any of the series’ previous books, and Lionsgate has already announced a film adaptation, tentatively set to release in late 2026.

The incredible enthusiasm with which Hunger Games fans—new and old—have (re)embraced the franchise transcends the literary world, making it one of the first global cultural phenomena of 2025. That’s very exciting to see, no matter how it may be judged in terms of literary merit. In a decade where our cultural landscape is rife with blatant and uninspired cash-grab sequelitis, the Hunger Games prequel books stand out for both their consistent quality and the narrative risks Collins takes, making each wholly fascinating in its own right.

Sunrise lets us into the point-of-view of 16-year-old Haymitch Abernathy, Katniss and Peeta’s dysfunctional and alcoholic but well-meaning mentor in the original trilogy. The book opens on reaping day—which is also Haymitch’s birthday—as he is selected as one of 48 tributes for the 50th Quarter Quell Games. Sunrise expands on Haymitch’s life in the Seam with his mother, little brother, and girlfriend, as well as the events of the Quarter Quell. This central narrative thrust is interesting enough but ultimately toothless. For most of the novel, Haymitch is convinced he will not outlast the Games. But readers know, of course, that he will be crowned the victor and that this will directly springboard the terrible personal tragedies that will haunt him well into adulthood. Most compelling is the psychological drama of the cutthroat Capitol politics working against Haymitch’s desperate attempts to ensure the safety of his loved ones. The intense pressure of the Games, as well as explicit threats from President Snow, enable him to mold a Capitol-friendly persona of the carefree “bad-boy” of District 12, echoes of which we can trace back to the seemingly laid-back cynicism of the Haymitch from the original trilogy.

As expected of any prequel, Sunrise is full of references to the previous books. Many characters reappear: Beetee, Wiress, Mags, and—delightfully—even Effie Trinket. We also meet a young Plutarch, ambitious and mercurial as ever, who sows the faint beginnings of the Rebel plot which will only come to fruition in Catching Fire. While these allusions are pervasive throughout the novel, I appreciate how Sunrise remains a self-contained narrative, allowing new readers to enjoy it without any prerequisite knowledge.

A broader issue, which may be more of a personal quibble, is Collins’ over-fondness of inserting songs and lyrics everywhere. These sections become especially egregious in the latter half, where you can expect at least a few semi-poetic digressions in every chapter. This predilection can be noticed in Ballad too, but in that novel, it makes more sense considering its second protagonist is a singer. In Sunrise, apart from serving as hammy foreshadowing, the overuse of lyrics renders them meaningless, distracting, and worse, boring. You can’t be blamed if your eyes begin to glaze over those italicized lines to carry on with the actual story towards the end of the book. These sections will doubtless work much more seamlessly adapted into visual or audio mediums, but their excess only serves to hinder one’s reading experience.

Regardless, Sunrise is a true meat-and-potatoes Hunger Games book—less ambitious than Ballad, but still as effortlessly entertaining as Collins’ other works. For all its flaws, it’s evident from this extraordinary success that the political impetus at the heart of its world still strikes a chord with readers of all ages. In crises, people gravitate to the familiar, to nostalgia. For many late millennials and Gen Zers, The Hunger Games—both the original trilogy and its glossy Hollywood film adaptations—stand out within our collective cultural memory as ubiquitously beloved fixtures in 2010s pop culture. And it’s no wonder that, at a time like this, we are so eager to escape into the confines of a comforting fictional dystopia rather than deal with the one we currently live in.