Mark Lawrence’s The Book That Broke the World is a disappointing read on every level. The story is weak, and the writing more so. On top of that, it doesn’t realize that its central debate has a foregone conclusion. Far more interesting questions on the subject of knowledge and memory could have been explored, but they’re neglected in favour of stale meditations on human evil.

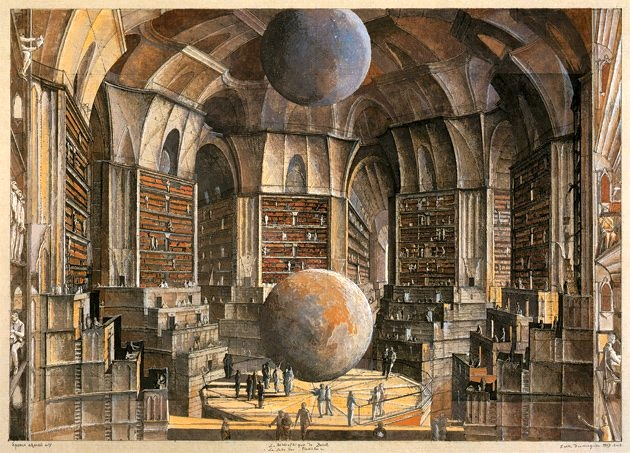

The Book That Broke the World is the second book in a planned trilogy. The first book of the series was gripping and the reason I tore into Broke the World so eagerly. It follows Liviria, a young librarian at a library which contains every book ever written, whether by humans or by other literate species. While exploring the Library, Liviria meets Evar, who has grown up trapped in one of the building’s chambers. The two are forced to flee their respective homes when a war between Liviria’s city and an army of wolf-like humanoids called canith escalates. The city is consumed by flames, an event that the Library’s records indicate has already happened several times before.

This is not a review of that first book, and I should, by all accounts, focus my summary on the events of its sequel. But that’s the problem: Broke the World gives me very little to summarize. The plot consists of a contrived series of adventures aimed at reuniting the characters who were separated at the end of the previous book: Evar and his siblings, who have finally entered a new chamber of the Library, Liviria’s Library friends, who have been sent to the desert where Liviria grew up, and Liviria herself, who is trapped in the form of a ghost. Broke the World doesn’t advance the story in terms of characters or worldbuilding. The only new elements in its wearying cycle of captures and escapes are the introduction of a few new monster species and an emancipation storyline that goes nowhere.

This sort of stagnation is a typical hazard for middle books in trilogies, which have neither the novelty of first installments nor the punchiness of finales. But Broke the World is flawed for more reasons than its flagging pace: it’s also badly written. Cliches and dramatic sentence fragments abound. Characters expound on their feelings, scorning the maxim of “show don’t tell.” There’s a Wattpad flavour to the writing that I’m completely baffled by—it makes no sense for an author with Lawrence’s experience or the resources available to him…like an editor.

What the book chooses to expend its energy on, instead of good writing or a compelling story, is fleshing out the series’ central argument about the value of knowledge, although the added depth doesn’t really make that argument any more compelling. The characters are involved in a war between the Library’s legendary founder, Irad, and his brother, Jaspeth. The current state of the Library—complete but unindexed, as well as difficult and dangerous to navigate—is the result of an uneasy compromise between the two brothers. Irad would prefer instantaneous knowledge for all, while Jaspeth believes that the Library should be destroyed. Jaspeth’s position is that knowledge learned without practical experience is dangerous because it would be untempered by wisdom, which is a practical skill.

Readers start out on Liviria’s side, in support of the Library, both because she’s the protagonist and because her opinion mirrors our own implicit belief in the importance of learning. That belief is challenged by the events of both books. In book one, Liviria’s people scour the Library for texts that vilify their enemy, the canith, to promote their own biased beliefs as fact. They build weapons with the help of ancient manuals for use against the canith, and these weapons end up burning down their city. In this book, we learn about the story of a brother and sister duo who accidentally kill the entire population with a gas attack, which they’d again learned to make thanks to the Library. One character notes that knowledge is inevitably weaponized and asks, “When evolution has shaped us to tribalism, how can we be trusted with the means to reduce tribes to dust?” Knowledge is portrayed as a weapon that can do real harm, both to its intentional victims and to its wielders, who deal with forces they are incapable of controlling.

The case against the Library, against knowledge that is too easily available, seems damning. Yet at the end of The Book That Broke the World, Liviria nonetheless chooses Irad’s side. What arguments does Lawrence put forward in her defence? The utility of knowledge for personal advancement, its ability to counteract misunderstanding or deception, and the chance to learn from past mistakes. Frankly, I can’t tell if these are supposed to be convincing. Knowledge only helps you succeed if you live in a meritocracy; Liviria, who lives in a world ruled by an ignorant king and is constantly given a hard time because of her peasant origins, owes her success more to luck than to learning. We all know from real-world experience with arguments on social media that misunderstanding is a very emotional issue and can’t be fought with facts alone. The history of Liviria’s city—which has been burned down and rebuilt so many times her people must dig through several layers of ashes whenever they open a new well—contradicts the claim that history allows us to avoid repeating past mistakes. Basically, Library access is doomed to cause harm because of the nastiness of human (and similar species’) nature, which is selfish, territorial, and obstinate.

To me, it felt like the book’s arguments were heavily supportive of the anti-Library view in a way that did not seem intentional. The harms of access to knowledge are vividly depicted, whereas the arguments in favour of the Library are generally weak. And yet Liviria, our moral compass, rejects this apparently insurmountable evidence. To be fair, she’s also shown proof that people don’t require much learning to still be downright horrific and that knowledge gained the hard way, from experience rather than reading, doesn’t guarantee compassion. However, ignorance limits the scale at which someone malicious can do harm—it’s the difference between a knife wound and an atomic bomb.

The book’s real argument for the Library comes down to a moral reverence for knowledge. Liviria admits as much when she acknowledges that her choice to fight for Irad isn’t rational but the result of her deep love for books. But faced with so many examples of the power of books to do harm, isn’t it worth interrogating that love beyond the amount that Liviria does?

In the end, the war between Irad and Jaspeth is a conflict between knowledge as a principle on one side and the inevitable malice of human nature on the other. Besides being imbalanced, this argument is also bland. I feel that there’s a missed opportunity here to think about our willingness to pursue knowledge without stopping to consider the consequences of what we might learn. I’d love to read a discussion of the ethics around developing a new, unregulated technology, and if it’s maybe unwise to run at full tilt into that field. Pinning the issues with the Library entirely on how bad actors choose to use knowledge is just plain boring. Yes, evil people are evil—we know! More interesting and controversial is the question of whether Liviria is complicit in their evil if she’s part of the system that unearths knowledge.

The good news is that there’s still plenty of time to course-correct. Maybe the final book will justify Liviria’s faith in the Library—or prove her wrong. Maybe it will tackle questions that are more worthy of the first book’s expansive worldbuilding. I don’t think The Book That Broke the World is a good book, and it’s certainly far below Lawrence’s standard, but I reserve judgment on the Library trilogy as a whole.