Many science fiction novels proudly display nominations or wins for what is considered the most prestigious award in English-language science fiction: the Hugo. The 2023 Hugo winners were announced on October 21st at the 81st Worldcon, the global science fiction convention under the World Science Fiction Society. While the Hugos hand out awards in many media categories, the most relevant are in the literary space. This year, Best Novel went to T. Kingfisher for Nettle and Bone, a dark fairytale published by Tor Books.

Best Novel is considered the highest literary award in a genre that often gets overlooked across the major literary accolades. Only two Pulitzer Prize winners have even been classified under the genre of speculative fiction, and no winners have been categorized as sci-fi. So in the absence of more mainstream recognition, awards like the Hugos are a big deal for sci-fi authors—but they might not be as traditionally prestigious as they seem. While a board of editors and media executives vote for the winners of the Pulitzers, the Hugos are a popular vote by attendees of that year’s Worldcon. Anyone can pay $50 to vote, and there is no requirement for voters to confirm they have actually read all the books on the list. As a result, the nominees and winners tend to reflect what novels are already popular in a given year, and previously winning authors seem to keep that momentum. These lax requirements may come as a surprise to those familiar with the Hugos’ reputation as the best of the speculative fiction awards. By traditional standards, the Nebulas would arguably be more prestigious as they emphasize reading every nominated novel, and voters must be members of the SFWA (and therefore published authors).

The Hugo winners are not the ultimate metric for popular sci-fi, however. Some highly acclaimed authors, like Kurt Vonnegut, have been nominated multiple times but never won. This could also be due to timing—Vonnegut’s most famous novel, Slaughterhouse-Five, lost to Ursula K. Le Guin’s seminal work, The Left Hand of Darkness, in the same year that she became the first woman to win both the Hugo and Nebula awards. Other voters have rightfully complained that the awards are just inconsistent and disorganized. With the Worldcon location changing every year, different committees are responsible for organizing both the convention and the Hugos, so little institutional knowledge carries over. Even as a popular vote, awards may not reflect the opinion of worldwide sci-fi fans as new committees can make modifications to the rules, and different fans are represented across different regions.

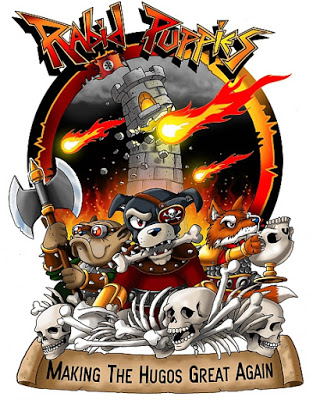

The Hugos as an institution were put to the test starting in 2013, the year the awards received the most attention outside of the sci-fi space. A controversial voting bloc called the “Sad Puppies” had emerged and was soon followed up by the “Rabid Puppies,” a sister bloc led by alt-right author Vox Day, “the most despised man in science fiction.” For five years, these Hugo voters organized around an anti-diversity nominee list for Best Novel, complaining that the nominations had been dominated by minority authors and progressive themes. Looking back, this claim is confusing, as every winning author since 1953 had been white, and 67% of them were men. It’s possible that the Puppies’ frustrations came from women authors winning the previous two years in a row, although this had happened multiple times since the eighties. Regardless of their motivations, the Puppies created a controversy that made the headlines and led the Hugos to rewrite their constitution to mitigate bloc voting.

Ultimately, these campaigns backfired. Every winning author after the first year of the campaign has been a woman, except for one. That exception was in 2014 when Cixin Liu became the first person of colour to win a Best Novel Hugo in its sixty-year history. N. K. Jemisin, the first Black author to receive the award, won the next three years in a row with her highly acclaimed Broken Earth trilogy, which has been praised for its thoughtful exploration of the themes of racial and ecological justice in a fantasy setting. Half of the last ten winning novels featured prominent queer themes, whether through a central relationship or in unique social constructs of gender. Ironically, the nonexistent “issue” the Puppies were mobilizing against became a reality after their failed efforts. This outcome could be seen as a point in favour of popular vote awards. As one Vox article stated in response to N. K. Jemisin’s third win, the Hugos are “generally seen as a barometer of changing trends and evolving conversations within sci-fi/fantasy (SFF) culture.” Jemisin’s consecutive wins were thus a firm rejection of the alt-right bloc by Worldcon attendees and the sci-fi community at large. That is something that might not have happened if the Hugos were run by an elite board of a few publishers and authors.

It’s understandable that people want awards to matter. In our competition-driven society, we are used to positive feelings as a response to institutional rewards. We feel associated with prestige when the things we like are given accolades. But institutions are not everything. The #OscarsSoWhite campaign brought attention to the correlation between the Academy’s racial demographics and those of the Oscar winners. Public opinion is changing to recognize that the dynamics inside prestigious institutions may not really reflect the objectively “best” works (if that can even exist). It could be a good thing that the Hugos are more representative of popular opinion when those voters choose to uplift voices that are being attacked. Maybe science fiction fans just need to rethink the purpose of the awards; at the very least, they make a good reading list.