Lidia’s Yuknavitch’s latest novel Thrust is an ambitious project, encompassing a startling range of characters, stories, and themes. It is not for readers seeking a regular plot and consistent characters. Rather, it is a very experimental novel, in which Yuknavitch has taken time travel and pushed it to historical (and even comprehensible) limits. Thrust (sort of) follows Laisvė, a girl born under a shadowy and controlling regime in the environmentally devastated remnants of modern society. The Statue of Liberty, for example, lives underwater, only the tips of her torch now visible. But if you think the story continues in this vein, you’d be incorrect—Thrust spans eras, generations, and fantastical realms, contorting time such that it is unrecognizable by readerly standards (maybe you’re a bit more open-minded, and these standards are merely my own). Time takes on a new meaning in Thrust, becoming one of the most interesting elements of the story.

Yuknavitch denies the idea that time is linear and that people remain consigned to one moment in time. Her characters might meet in one era, like when Laisvė and Michael (a troubled youth in a juvenile detention hall) meet as teenagers, and reconnect at different times and at different ages later in their lives, whether this be two hundred or twenty years in the past or future. The next time Michael meets Laisvė, she is a young girl and he is a grown man. This chronological confusion is perfectly acceptable by Yuknavitch’s standards—it accentuates her point that time does not work as people normally perceive it.

I have a few different angles from which I considered this point, as I initially struggled to understand it. After finishing Thrust, I was frustrated by the lightly-sketched characters, random ethnographies and “Cruces” sections inserted throughout, and the confusing plotline that tangled people, objects, stories, and magical talking whales, turtles, and worms across centuries.

But part of what makes Thrust interesting is that characters and a linear plot are beside the point. Yuknavitch tells a story that juggles with climate change, authoritarian government, immigration, and Indigeneity in a unique and refreshing manner, speaking to the historicity of these elements by blending past, present, and future until all are unrecognizable. Few things ground the reader to a sense of time or place in the novel, although one powerful motif is the Statue of Liberty, which exists when Laisvė visits the immigrants who are employed in constructing it, when Laisvė is a young girl and only the golden tips of the statue’s torch can be seen, and when it is completely underwater and a new, aquatic society has developed to face the environmental challenges of the future. Modern responses to many contemporary issues like climate change, immigration, and Indigenous rights do not properly account for the past; it seems to me that by forcing all chronological perspectives into a nonlinear sequence, Yuknavitch is advocating for a more balanced and historical approach to these issues.

This nonlinearity brought me to my second consideration, which is that Thrust fights back against the concept of settler time. Settler time, a concept developed by Mark Rifkin in Beyond Settler Time: Temporal Sovereignty and Indigenous Self-Determination, is driven by the appropriation of Indigenous lands and the elimination of its native people, and relegates Indigenous people to the past both in narrative and everyday life. Yuknavitch’s ethnographies, scattered throughout the novel, speak to her concern about this; she describes the destruction of Yakut land and also takes colonial time into consideration as she incorporates the stories of many immigrants into the flow of the narrative, even going so far as to quote Emma Lazarus’s The New Colossus.

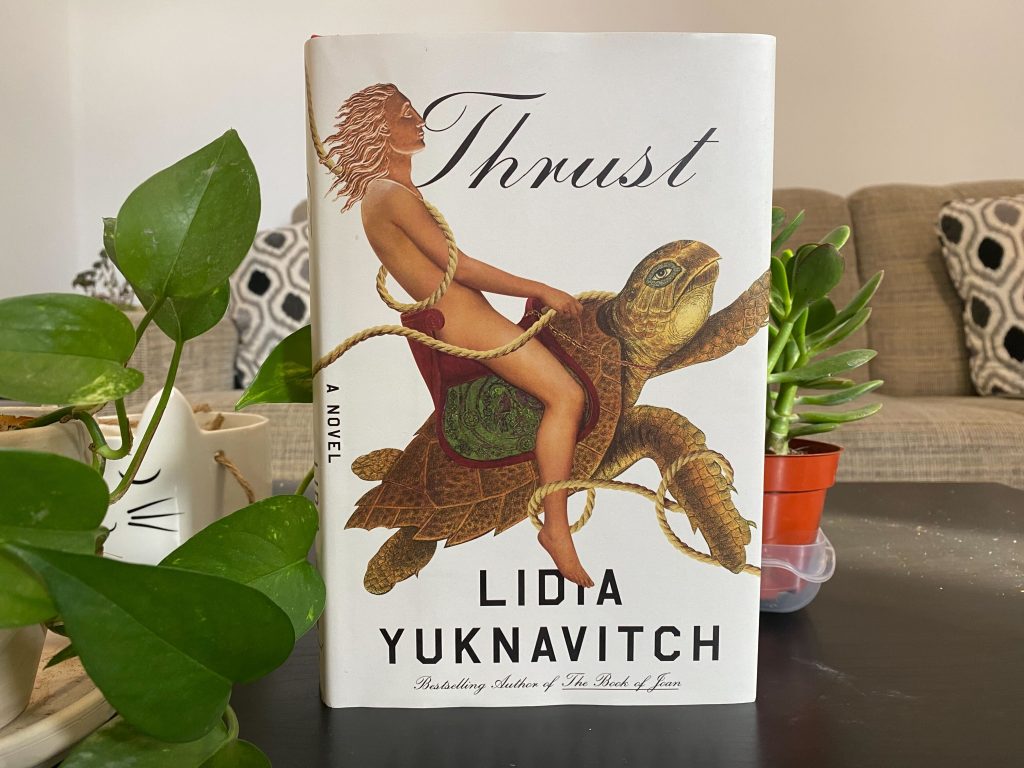

Rather than relegating BIPOC and immigrants to the past, she uses their methods of storytelling to support her story, incorporating them throughout the construction of her narrative. Betrand, for example, is a talking and time-travelling turtle who helps Laisvė as she transports important objects and people through time. His character is particularly interesting because he seems to exist as a reference to, or symbol of, Turtle Island, the name by which some Algonquian and Iroquoian peoples refer to North America. Although Yuknavitch never explicitly mentions this, Betrand is central in guiding Laisvė through her travels, and his understanding of time, history, and nature supplies her with the skills she needs to travel through time and space. Yuknavitch ties Indigenous people, stories, and ideas to her plot and to the saving of Laisvė’s world. She does this with the many immigrants of the story, too.

Yuknavitch’s novel is a challenging, although fairly successful, experiment. Time usurps and alters every aspect of the novel—although this is often to the detriment of the other elements of the story. We learn little of Laisvė and the other characters who are introduced throughout at breakneck speed, jumping into their perspectives with little indication and no change in authorial voice. Nevertheless, these neglected elements (if they are indeed neglected—this could also be Yuknavitch’s design) emphasize the importance of interpretation in the novel, indicating that just because we perceive people and their history in a certain way does not mean that there aren’t another hundred perspectives that each fight to assert their own truth on reality.