First instalment of a new ImaginAtlas series looking beyond the Anglo and Francospheres to spotlight underappreciated and exciting works of speculative fiction from all around the world!

Vampires in Western media are largely romanticized, especially since Bram Stoker’s Dracula hit the scene. Usually, this Western vampire is a pale, stoic man with a powerful jawbone and an insatiable desire for the female lead. In China, however, the model of a vampire is a stiff, blue, hopping one- not exactly the characteristics that make up a teenage heartthrob. As time passes, the fear of the vampire has lessened, and the drama of a romantic vampire has taken its place. The wildly popular reception of media like Twilight, True Blood, and The Vampire Diaries has all been contingent on the vision of a beautiful and irresistible, albeit haunting, vampiric love interest. The figure of the vampire is not, by any means, unique to Eastern European origins and is, in fact, rather ubiquitous across several cultures. One such formulation of the vampire, as mentioned above, originates in China during the Qing Dynasty. What happens, then, if we consider a vampire model that doesn’t adhere to the Eastern European-derived figure of the undead bloodsucker? How might romance differ if the vampire could not blend into human society as well as a modern Western vamp can?

The global consciousness has perceived vampires as a symbol of sin since their very conceptualization, not only through a Christian lens but in the case of some of the Chinese vampires, as an antithesis to Buddhist morals. The design of evil taking the form of a specific sin shows Western media’s preoccupation with a fear of anything which subverts conservative ideals: vampires are dangerous, tragic, sexually liberated, and above all, symbols of social disturbances. The vampire archetype across cultures embodies the fear of sin and diverting from the religious norm. The Eastern European formulation of a vampire is that it cannot die and, therefore, cannot go to heaven, and the Chinese vampire also cannot die and, therefore, exists outside of the Six Paths to the reincarnation of Buddhist cosmology.

The Chinese folkloric figure of the jiāngshī, or Chinese Hopping Vampire, does not immediately evoke a pallid smoke show sparkling in the sun but it exists alongside vampire media, nonetheless. The jiangshi are reanimated corpses much like their Eastern European counterparts, but they are notably stiff, having succumbed to rigour mortis, and have a bluish tinge to their skin. In fact, the character ‘jiang’ (僵) of “jiangshi” means ‘hard’ or ‘stiff’. The jiangshi do not sashay around, but rather, they hop, these Chinese creatures can also be in various signs of decay when they are reanimated, which lends itself to certain haunting depictions of a stiff, rotted human hopping around with outstretched arms and stealing one’s qi, or “life force” in lieu of blood. In early Qing portrayals, they are often depicted as wearing the traditional Confucian scholar’s robes of that period. Given these traits, it seems difficult to imagine a romance with a jiangshi, especially a romance that would remain undetected by others.

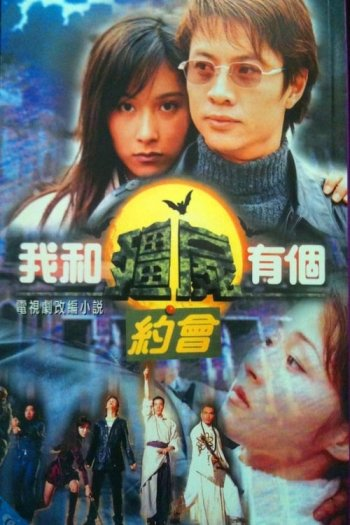

However, the Chinese series My Date with a Vampire (我和殭屍有個約會) proves that the jiangshi can have a wildly successful spot in the vampire romance motif as well. Airing at a similar time to many Western pop-culture hits depicting blood-drinking baddies (such as Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Angel, Charmed, etc.), the Hong Kong series My Date with a Vampire made (MDwaV) its debut in 1998 on Asia Television (ATV). The story goes something like this: Fong Kwok-wah (who later changes his name to Fong Tin-yau) is, alongside Yamamoto Kazuo and an adorable child named Fuk-sang, bitten by the progenitor of all vampires in 1938. In 1998, present day, the boy pretends to be Fong’s child and they live their lives as regular humans —who are immortal and occasionally drink blood to survive— until they meet the heroine of the show, Ma Sui-ling, the heiress to a clan of sorcerers who wishes above all to rid the world of the supernatural. Of course, regardless of location of origin, no vampire media would be complete without a love triangle. Fong falls for sorceress Ma and must compete with her good friend Wong Jan-jan for her affections. Forget team Edward or Jacob, I’m talking team Wong or team Fong. Shenanigans ensue as Yakamoto attempts to turn every human into a vampire. It is up to Fong and Ma to stop the vampires running amuck through the streets of Hong Kong.

While MDwaV does not follow the lore of the jiangshi exactly, it blends the Western media’s vampire depictions with the traditional jiangshi lore to create a love interest that combines the supernatural abilities of the jiangshi with the vicious beauty of the Eastern European vampire. The vampires of MDwaV are immortal (because they exist outside of Buddhist cosmology and cannot be reincarnated) and must feed on human blood to survive, but do not take on the blue corpse-like appearance associated with the traditional jiangshi. Instead, the jiangshi in MDwaV, like the Eastern European vampires, are gorgeous porcelain paradigms reflexive of the beauty standards of their surrounding culture.

The clear popular success of MDwaV (as evidenced not only by reviews averaging 8.2/10 on IMDB but also by the sequels which continue to emerge) shows that there is still an audience for portrayals of vampires that subvert the European formulation of vampirism. While the jiangshi—hopping, blue, and stiff—are not necessarily paradigms of attraction, with a little tweaking here and there they are still the basis of a widely prolific media source, which certainly gives Eastern European vamps a run for their money.