Third instalment of a new ImaginAtlas series looking beyond the Anglo and Francospheres to spotlight underappreciated and exciting works of speculative fiction from all around the world!

When aliens invade the Earth, they tend to go for the same places: in American movies, New York or L.A; in Doctor Who, London; in tokusatsu, Tokyo. This is obviously due to simple, practical concerns: it’s much easier for an author to write about their own city than one halfway around the world. It’s also cheaper to film in the streets outside the studio than to take a plane and get a permit to shoot abroad. When a few (wealthy) countries dominate media production and distribution worldwide, though, this starts to get a little problematic. The domination of these First World narratives starts to feel stifling—it’s enough to make people from the rest of the world ask, “Why can’t we get invaded by the saucermen?”

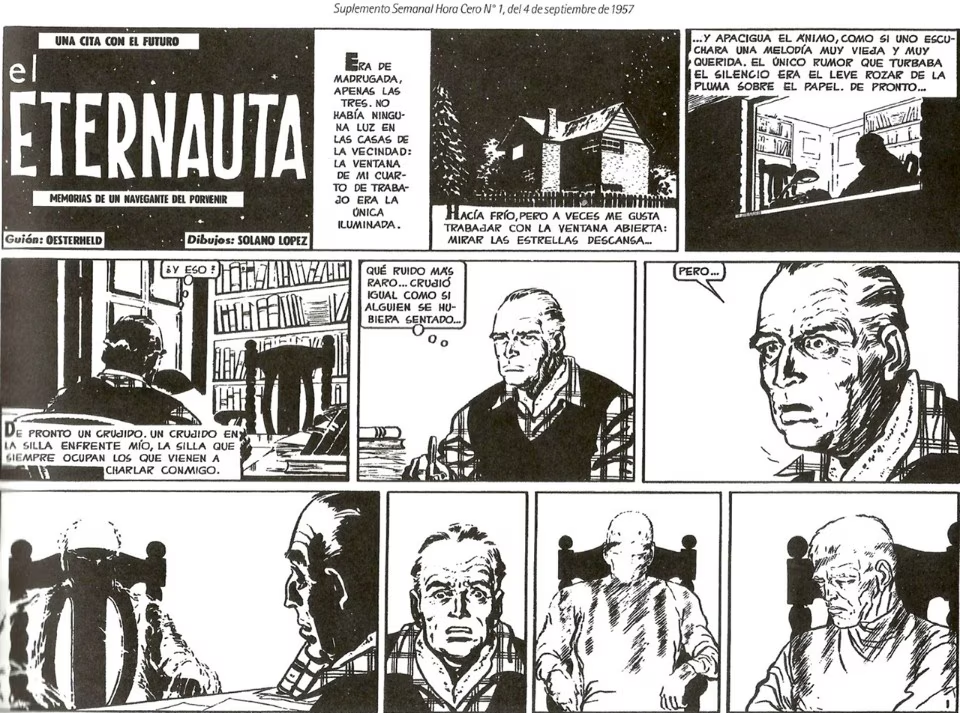

Hector Germán Oesterheld and Francisco Solano López’s acclaimed comic strip El Eternauta is a dazzling corrective to that tendency. Here is an alien invasion story every bit as rich and layered as the best of them, from War of the Worlds to Invasion of the Body Snatchers, and one that is also unapologetically Argentine in setting and sensibility. Its commitment to being grounded is unceasing, never minimizing the gruelling struggle of the protagonists, even as it persistently refuses to reduce them to heroic, uncomplicated figureheads. This is as close to the harsh reality of organized resistance as any story featuring giant man-eating insects has ever come—which sounds like a backhanded compliment, but it really isn’t.

The title (“The Eternaut” in English) refers to the protagonist, Juan Salvo, who at the very beginning of the strip appears to the author himself from the future (or perhaps another dimension) and dictates the tale we’re about to read. It begins innocuously enough with a group of friends in Buenos Aires playing truco, a much-loved card game among Argentines. Outside, an eerie snowfall descends—not an entirely uncommon sight in the city, but enough to be notable—and soon begins killing everything it touches. Juan and his friends are horrified but nevertheless soon make plans to search for survivors. This leads to the most iconic image of the series: Juan, attired in his self-made isolation suit, walking through the desolate, corpse-strewn streets of Buenos Aires.

This would be a chilling scene in any setting, but a large part of it for me—and probably any other reader who’s ever been to the picturesque Argentine capital—is the faithful rendition of the city’s landmarks, covered in a thin, undisturbed sheet of snow and bereft of life. For Montrealers, imagine an empty Sainte-Catherine or Sherbrooke in broad daylight (the snow you don’t have to imagine). It makes the ensuing SF saga even more effective than it would be otherwise because the more far-flung action is consistently grounded in a very real sense of place.

Here are just a few examples. The neighbourhood where it all begins is recognizably Vicente Lopez, a quiet suburb of Buenos Aires where the last thing one expects is homicidal alien space beetles. Later, the heroes make their base in Avenida General Paz’s huge roundabout. Its prominent location helps orient every subsequent development. Towards the end of the story, they encounter the terrifying multi-fingered servant of the invaders in the gazebo at Barrancas de Belgrano Park. Solano López’s art already renders the villain in sickening enough realism, but seeing him lurking in such a recognizable and picturesque place somehow freaks me out even more. I doubt I’ll ever visit that gazebo and not think of that scene again.

The period it reflects, too, is an integral part of the story. Juan Salvo’s world may not be our own, but Oesterheld goes to great pains to tie this tale of guerrilla warfare to the midcentury Argentina it was published in. Said Argentina was also embroiled in an ongoing struggle between left-leaning freedom fighters and an oppressive, foreign-backed power. The country’s military junta, funded and trained by the CIA, killed or disappeared tens of thousands in the so-called Dirty War, including Oesterheld himself, probably for writing this very comic strip. Suffice it to say, El Eternauta is very aware of its applicability to a real-world context. Given the ever-present danger of censorship and silencing, Oesterheld and Solano López’s commitment to their ideals becomes even more meaningful.

It’s also a remarkable example of the power of fiction in combating repressive regimes. Juan’s iconic isolation suit soon became a staple of defiant graffiti during the dictatorship, providing the repressed population with an image that perfectly encapsulated the spirit of resistance and, at the same time, felt distinctly homegrown. And if you think that relevance has faded since democracy returned in 1983, think again. The recent election of Trump/Bolsonaro wannabe and avid dog cloner Javier Milei in Argentina, who has downplayed the junta’s crimes, has renewed fears of censorship and repression in the country.

Yet the perfect antidote seems to be on the horizon: a Netflix adaptation of the comic strip starring Ricardo Darín, king of Argentine cinema. This new series, which already looks great from what we’ve seen so far, might well touch off a new appreciation of El Eternauta in Argentina and abroad. After all, its storytelling and subtext may be rooted in a certain time and place, but its call for resistance is truly universal—and perhaps more needed now than ever.