“Mother! Bring me into the world.”

And so, the marvellous Kirikou is delivered. More specifically, he delivers himself, crawling into the world with perfect speech, a sureness to his steps, and a list of questions to be answered: “Mother, where is my father?… Where are my father’s brothers?… Where are my mother’s brothers?” To each inquiry, baby Kirikou’s mother replies soberly: “They went to fight Karaba the Sorceress, and she ate them.”

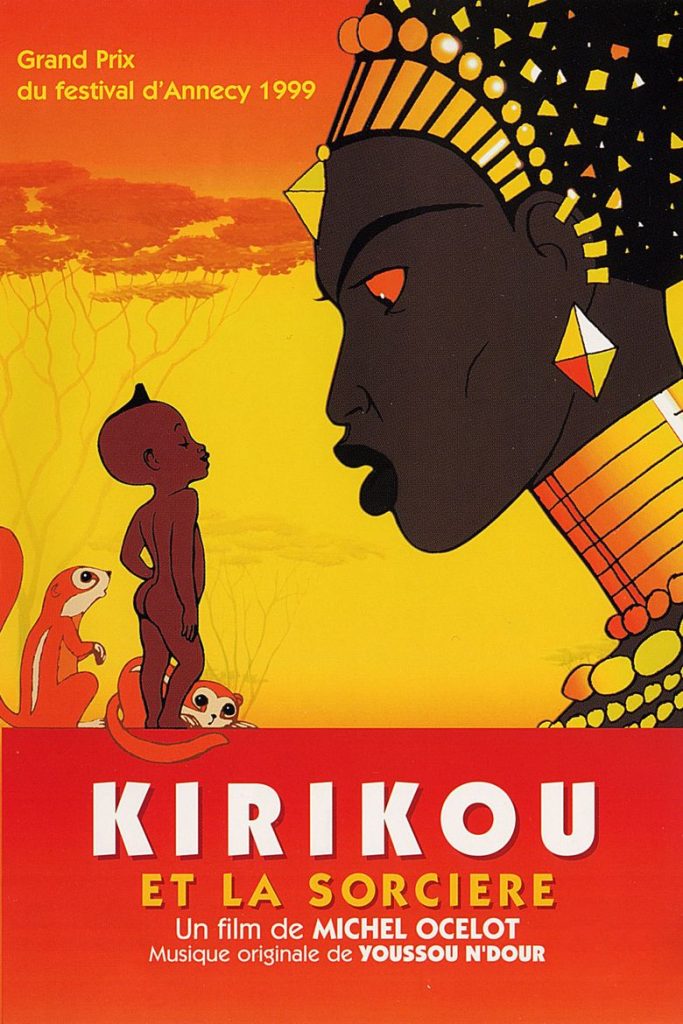

Thus, baby Kirikou embarks on a quest to save his community from an evil witch; he slips, he falls, but nevertheless persists, earning wisdom, courage, and compassion far beyond his years (or should I say days? He was literally born yesterday, after all). Even 25 years later, Kirikou et la Sorcière (Kirikou and the Sorceress) remains a champion of true African representation in the fantasy genre. At the time of its release in 1998, Kirikou marked the close of a century stained with the violence of colonialism, cultural erasure, and revolution across the continent. European missionary work in the region had characterized ancient tradition as satanic and crude, and these misrepresentations endured notably in the history of cinema. Take King Solomon’s Mines, for example, adapted for the screen four separate times, each acting as a piece of pro-colonial propaganda. Or, The African Queen, which, even with status and acclaim, exoticizes its East African setting to the point of pure invention.

With such unsavoury predecessors, the French-language animated fantasy Kirikou et la Sorcière is a feat of African storytelling on the silver screen. As a counter-narrative to the orientalization of African cultures, Kirikou presents its magic with fantastic whimsy and charm alongside strong values of compassion and community. Despite its European production, Kirikou triumphs as a profound family story with strong morals and a killer sense of humour, all true to its Senegalese setting. The villagers, while often fallacious, are never ridiculed by the lens of the camera, and the female characters, dressed with casual female upper nudity foreign to many audiences, are never sexualized. The film wholly rejects a century’s worth of distortions placed upon Africa’s landscapes, peoples, and cultures to great success.

It’s easy to embrace ignorance; it is bliss, after all. But Kirikou asserts that when you refuse to seek truth and understand the full story, tunnel vision and false assumptions will steer your own demise. The boy wonder refuses to join his community in accepting Karaba’s villainy as a fact of life. He interrogates his village on the source of her malevolence, and they carelessly respond that it should not be questioned. After near-drowning to save the village from another of Karaba’s “tricks,” Kirikou claims she is the most wicked of all the village. His mother suggests instead that she simply has more power. Surprisingly, Kirikou’s mother rejects the basic idea of good and evil with which her community defines the world. She is the first to admit her ignorance, and subsequently, she guides Kirikou towards the Wise Man of the Mountain for answers.

If Karaba is the Wicked Witch of the West parallel, the Wise Man is the Wizard of Oz in Glinda’s gleaming dress. Hidden in the mountains, Kirikou finds singing birds perched along a grand passageway leading to the Wise Man, sitting tall in contemplation. Here, Kirikou finally finds the treasure of truth he seeks: the wicked, powerful, no-good Karaba attacks… because she’s scared. The root of this conflict, rather than evil or good, power or control, is fear. Karaba, still suffering from a violent attack from a group of men in years past, is now jaded against humanity. She doesn’t care about improving her condition or ending her suffering because of the power she’s developed as an outcast. Unfortunately, this power comes at the cost of potential love, care, and community.

On the flip side, the village fears Karaba even though she’s innocent of their accusations. They refuse to learn the truth about her because it’s easier to live in fear than to extend a hand towards the enemy, to question the narrative you’ve embraced for so long. It takes an infant, underestimated at every turn, to finally make a change. Kirikou’s Herculean quest for the truth takes him through tunnels, forests, and caves far from home—not to slay the monster but to understand her. In the end, only Kirikou holds the truth of the Sorceress. Only he knows how Karaba suffered and how her pain forced her into isolation. Ultimately, it is their love and understanding for each other that ultimately saves them both.

This refusal of mutual understanding is a startling reflection of the film’s reception. Kirikou et la Sorcière was banned from release in the U.S. and U.K. due to its embrace of nonsexual nudity. Despite the positive messaging and great success at animation festivals around the world, it was deemed unsuitable for children. American reluctance to authentic West African storytelling sits in perfect harmony with the brutal history of anti-Black racism in Hollywood. But fundamentally, it reflects a “refusal, intentional or unintentional, of an audience to communicatively reciprocate a linguistic exchange owing to pernicious ignorance,” as philosopher Kristie Dotson defines the practice of cultural silencing. Kirikou was a message that many Western audiences refused to hear.

But in today’s age of streaming, our access to media is, in some ways, becoming less and less restricted by the politics of production. We have the power to look to the margins for independent stories and new voices on screen. Kirikou is not on Netflix or any major streaming service, but you can find it today on Kanopy or Internet Archive. Let the young hero leave you with a final lesson: never underestimate your ability to create change. So read African fantasy, watch the films, learn our mythology—who knows, you might find a brand new favourite.