Speculative worldbuilding is no easy task. It can be challenging for authors to balance descriptions of otherworldly environments, explanations of relevant history, and demonstrations of magic systems or other mechanics, all while communicating an engaging plot. This can be especially difficult in science fiction and fantasy, where readers often have no previous knowledge of the ideas and settings that compose the story world. To ensure enough context is present, authors sometimes fall into the trap of over-exposition, where every reference to something new is followed by a multi-paragraph explanation that rips the reader out of the narrative and plops them in a fictional history class. Authors who want to avoid this may end up swinging too far the other way, where dozens of place names and character titles are dropped with no background information, leaving readers frustrated at the mental effort it takes just to keep track of the plot. But there is one shockingly simple way to avoid both of these issues: letting the main character be completely clueless.

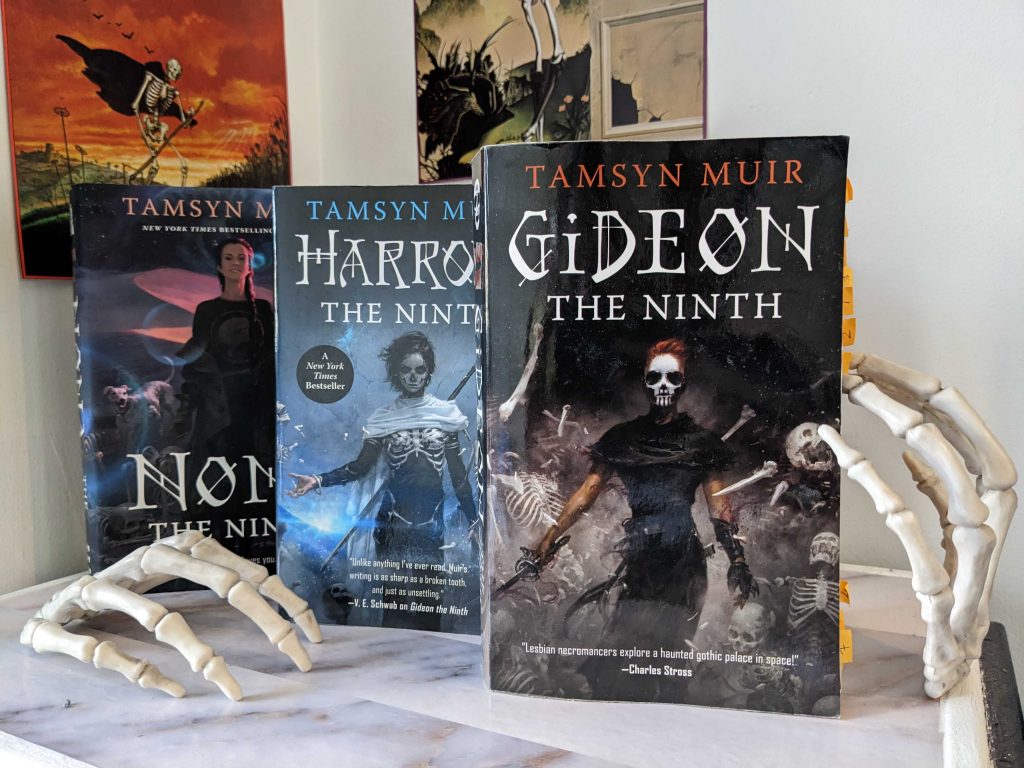

Enter The Locked Tomb. Tamsyn Muir’s debut science-fantasy series has captured a dedicated audience since the release of the first book, Gideon the Ninth. Part Greek epic, part Catholic-Gothic horror mystery, and part early-2000s Tumblr, The Locked Tomb is notoriously difficult to summarize and even harder to explain, with most fans reverting to a shortened version of the blurb “lesbian necromancers in space” to market it. Muir’s worldbuilding is just as complex as her storytelling (one book is primarily delivered in nonlinear second person from an unreliable narrator), with the first line of the series establishing the time period as the “ten thousandth year” of the ruling Emperor. While The Locked Tomb’s settings aren’t as sweeping as those of franchises like Star Wars or Doctor Who, they continue to expand as the series progresses and characters find themselves in starkly changing circumstances, thanks to galactic threats and tangled interpersonal relationships. The main setting of the Empire of the Nine Houses is built on necromancy, which is presented as not only a dense science but also a phenomenon that dictates all social dynamics. It would be very easy for Muir to stumble while relating the nuanced mechanics, long history, and intricate character connections, especially as each book in the soon-to-be four-part “trilogy” is told from the perspective of a new main character. But she manages her worldbuilding in a creative and effective way.

As the titular main characters change, one thing stays the same: they are always the most unqualified person to be narrating the plot. Gideon the Ninth introduces the world of the Nine Houses from the view of Gideon Nav, accurately described by one fan as a “dark academia jock, attending on sports scholarship.” Gideon is a new entry into the canon of “least knowledgeable characters,” a technique famously used by Tolkien to connect the reader’s experience to that of the main character through “broken references” that both can uncover together. As a clueless main character, Gideon could care less about necromancy, preferring to spend her days working out, sword fighting, and reading her pinup magazines (“for the articles,” as she asserts). But when she is forced to become a cavalier and accompany her House’s heir to a series of necromantic trials, Gideon is thrust into the world of academic necromancy firsthand alongside readers. Because Gideon has a limited understanding of the world’s primary mechanics, Muir’s explanations of necromantic science are not only for the reader’s sake. Gideon’s lack of knowledge also aids the plot, as she (and the audience) put the pieces together more slowly, preventing any early reveals. The audience learns at the main character’s pace, which fosters engaging worldbuilding that never takes us out of the story.

In the subsequent Harrow the Ninth, Harrowhark Nonagesimus, the new POV character, does have a deep and intimate understanding of necromancy. But having come from an isolated House on the edge of the system, she has limited knowledge of the true history of the Nine Houses and the actions of the broader Empire. While the audience may be excited by the introduction of new characters and settings that can provide that information, Harrow is not in the same position. She spends the course of the book being put through the wringer, and holding onto her sanity with every passing day is her primary concern. Because of this, readers’ main access to more detailed history is through the conversations Harrow overhears. A lot of characters talk at Harrow, and she is frequently not in the state of mind to ask follow-up questions.

Harrow the Ninth is definitely a hair-pulling read, but instead of causing readers to give up in frustration, knowing the main character is equally disoriented puts them in the same boat. Muir’s creative choices show that she trusts her readers are capable of deeper thinking as she keeps them invested while encouraging them to figure out what’s happening themselves. The subtle details that are revealed are intentional and effective. By the third book, Muir partially shifts to info dumping, spending half the chapters with one character narrating the entire background history of the universe to another (thanks to circumstances that let this work naturally within the plot). Because readers had been theorizing about the history from the hints they were given in Harrow the Ninth, this info dumping is actually enjoyable—and comparing these chapters to older blog posts shows that many readers’ theories fell extremely close to the truth. The Locked Tomb proves that the uninformed point of view doesn’t leave audiences lost with no knowledge, but can do the opposite, by pushing them to accurately uncover hidden meanings on their own.

Many fans of speculative fiction love the genre precisely because of the worldbuilding and can be let down when its presentation falls through. Authors should have more confidence in their audience’s ability to navigate a text without hand-holding, and recognize that many people consider that journey the most captivating part of a story. At the same time, not all authors can communicate limited information effectively. Lengthy novels such as The Priory of the Orange Tree—which alternates between three different POV plots in the first two chapters, all while referencing multiple locations and introducing cultural practices without much elaboration—risk audience frustration if the main characters do not share the reader’s lack of knowledge. Uninformed narration can treat readers as if they are characters, allowing them to participate in the adventure as well – and who wouldn’t want to embrace that escapism?