This is the first part of a new series exploring comics history from the 1930s to the present by considering crucial works from each period. Whether you’re a comic-shop virgin or an obsessive collector, you’re sure to learn something new and surprising!

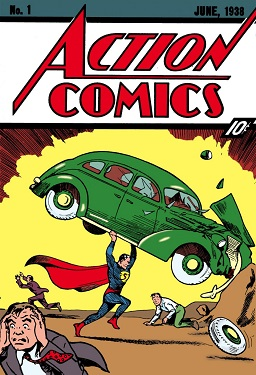

See it now: a man in tights and a cape lifting a car above his head, gangsters fleeing in terror from the dread figure. This is the cover of Action Comics #1, the first glimpse we ever got of Superman—easily the most iconic superhero of all time—and thus the obvious starting point for this series’ journey through the history of comics. Though there were already costumed ‘proto-heroes’ like the Phantom and Prince Valiant, who fought and snuck their way through an assortment of newspaper strips, the first to combine the requisite costume, the powers, the identity, and the medium (a bound comic book) was unquestionably Superman.

Yet paradoxically, his historical background (and that of the genre as a whole) now languishes in relative obscurity, even as his descendants dominate cinemas worldwide. If we want to really understand this most modern of archetypes, we must closely interrogate what lies at its heart. And that means looking long and hard at the circumstances from which it first emerged—and all the ingredients that went into its first formulation. This is what this series endeavors to do.

But back to the car image for a moment. To us now, it comes across as a standard instance of the good guy saving the day, but, as Grant Morrison has noted in their renowned comics history Supergods, readers at the time could have had any number of reactions to it. The most obvious one would be — who is this terrifying figure? Is it on the side of good or simply engaging in wanton destruction? Let’s not forget that the ‘30s produced a far more sinister form of ‘superman,’ one that would wreak devastation throughout the globe by the decade’s end: the Nazi Ubermensch.

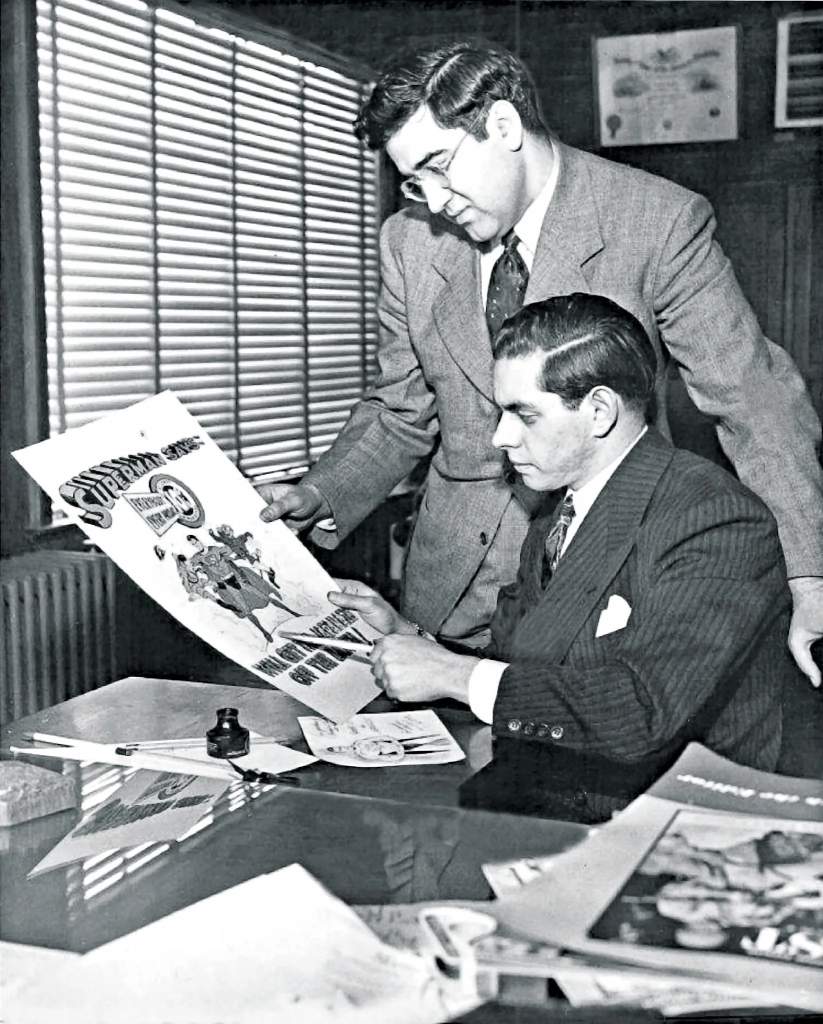

Did Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster, both North American Jews, have this in mind when they conceived the character? Neither ever admitted as much, but perhaps it’s telling that the character’s first iteration, debuting in the self-published fanzine Reign of the Superman in 1932, was a gratuitously violent and openly villainous being—a test subject who goes on a rampage after gaining superpowers. This sense of danger, equally alluring and frightening, is present in Superman’s first few appearances, though by now, decades of parody, mischaracterization, and Bowdlerization have almost succeeded in burying it entirely.

Even today, that primordial violence (the same one that was unleashed in the first blood-soaked half of the 20th century), no matter how well hidden, remains an intrinsic part of the foundations of the fully-developed superhero myth. Only on rare occasions does that quality peek through and startle us with the associative power of characters and symbols we now regard as mundane (did you ever notice how much the famous ‘S’ shield looks like a military insignia?). It should remind us of the archetypes we’re playing with here—not merely entertaining fictions for children, but rather personifications of terrifying psychological forces made manifest in the modern world.

True to its title, Action Comics #1 is wall-to-wall with non-stop, delirious action. It covers Superman’s entire origin story, from Krypton to the tights, in a single page, then launches into a succession of sordid crime stories that would not have seemed out of place in the noir magazine Black Mask. What distinguishes these tales—including an attempted lynching, a case of domestic abuse, and an encounter with gangsters in a dance hall—from the reams of similar material found in contemporary pulps is the mere presence of Superman.

Pulp heroes like Doc Savage or the Avenger sometimes exhibited superhuman powers but still mostly relied on their wits, fists, and firearms to save the day. The Man of Steel operates on another level entirely. He rips open a steel door to get an innocent man reprieved, leaps off a rooftop holding a criminal by one leg to make him talk, and throws a wife-beater against a wall so hard it practically crumbles.

Present-day comics readers will note that this is substantially below Superman’s current power levels (over eighty years of ‘power creep’ will do that), but his capabilities here are still so far ahead of any of the mundane threats he faces that most conflict is resolved within a few panels. Unlike his pulp contemporaries, he is not needlessly cruel, but still seems to delight in tormenting those who deserve it. As Supes chases the gangsters in their car, just before the iconic cover moment, Shuster draws their faces contorted into panic, while Siegel’s dialogue has them exclaim, ‘STEP ON THE GAS! HE’S CHASING AFTER US!!!’ and ‘IT’S THE DEVIL HIMSELF!’ Even after he saves Lois Lane, Supes has to reassure her, ‘YOU NEEDN’T BE AFRAID OF ME. I WON’T HARM YOU.’

One is reminded of the eldritch angel in the Book of Ezekiel, so far from the typical harp-and-wings depiction that it has to tell the prophet, ‘Be not afraid.’ Such power may be unearthly and frightening, but at least it’s on our side. The raw, newborn Superman of Action Comics #1 is the same. Before his sanitization in subsequent decades, he was pure modern dynamism given human form, descending into a familiar urban crime milieu like a wrecking ball. Some have called him a coded Jewish or proletarian avenger, but that narrows his appeal; ‘38 Superman is nothing less than the personification of the radical new powers unleashed by the twentieth century.

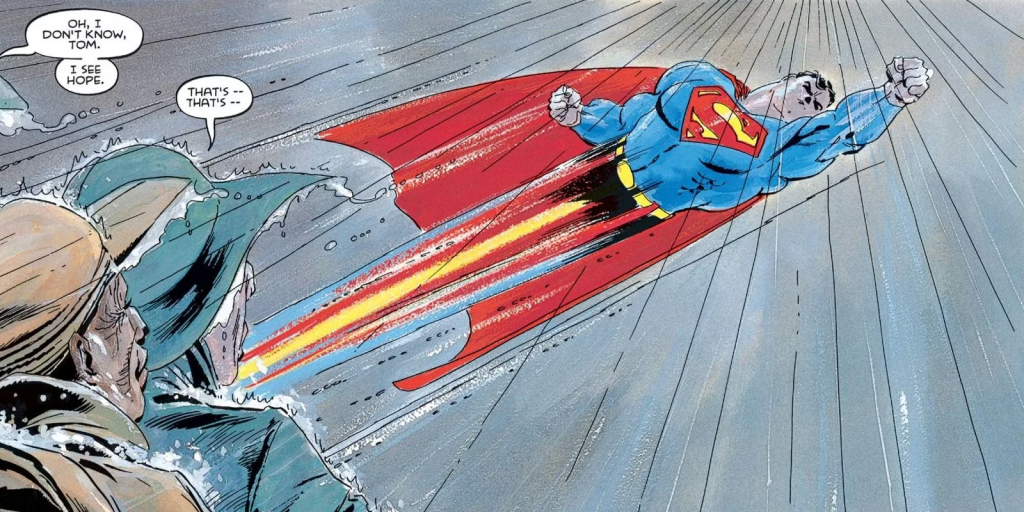

Is it any surprise that early Superman stories consistently pit him against cars, trains, firearms, dynamos, and other products of modern industry? This approach was so effective in establishing the Man of Steel’s power that it would be repeated in the 2011 Action Comics reboot, also by Grant Morrison (who clearly understands the character better than most). Superman is just that—a man greater than man, a concept now more credible than ever due to rapid technological advances (and less savory beliefs of the time like eugenics).

Yet he still has one foot in ancient myth, just as the self-declared Supermen in the Third Reich extrapolated Wagnerian opera and Germanic legends to justify their inhuman doctrine (not to mention the Imperial Japanese conquerors whose delusions of superiority relied on repurposed Shinto beliefs). Ironic as it may seem, superheroes and fascism, natural enemies in WWII propaganda, were born almost simultaneously from the same soup of collective anxieties and obsessions. Some may hold that the former emerged as an antidote for the latter, but that implies too much purpose in their creation; both are simply products of their time, put to opposing ends—though history has shown which had the greater staying power.

Siegel and Shuster’s possible mythic influences are various: the orphan origin story vaguely suggests Moses, the super-strong champion is seen from The Epic of Gilgamesh to the Biblical Book of Kings, and the folk hero who punishes evil in disguise (often brutally) has too many variants to count. Regardless, it speaks of a time when turbulent modernizing change often reached back paradoxically into a past imagination.

The Golden Age of Comics (roughly from 1938 to the war’s end in 1945) was characterized by the many superheroes who emerged in the rush to copy Superman’s success. These competitors, as a rule, were far less shy about their debt to world mythology. The original Flash, Jay Garrick, wore Mercury’s hat and boots, while the first Green Lantern, Alan Scott, drew his power from Aladdin’s magic lamp. Fawcett’s Captain Marvel, AKA Shazam (who briefly outsold Superman in the 40s), drew his power from Hermes, Zeus, and four other gods. Batman is a notable exception, closer to genuine non-powered pulp heroes like Zorro and the Shadow than any of his peers.

What, then, makes Superman unique besides his age? If his signature blend of ancient influences and modern capabilities was almost immediately ripped off (and still continues to be), then is his significance now purely historical? Can that dazzling quality that made his first stories so compelling be reproduced today? I believe it can. Because as much as he may be derided as square and bland by many readers today, Superman still has something none of his rivals do—the full package. In a sense, he encompasses every other superhero in existence.

Not only does he boast almost every mainstream superpower (except telepathy), but he also enjoys a superior mythos. His secret identity, origin story, love interest, villains—these are all first-class, not to mention so iconic most people can name them. If his stories come across as rote, this is simply the result of authors leaning on excellent material without bothering to fully exploit it. When they do, the results are magical; just look at All-Star Superman or Superman for All Seasons or Superman Smashes the Klan or any number of other modern classics.

Perhaps the best way to put it is that every superhero wants to be Superman. He’s the Platonic ideal of what a superhero can be. What’s more, he epitomizes the Golden Age, when comics were a true mass media sensation, something they can only aspire to now. In fact, his titles have been some of the few to display consistently strong sales through all the ups and downs of the comics industry. In a time of antiheroes of various shades of gray, Superman remains unambiguously, grandly heroic. In a time of major reimaginings, he always seems to default back to his standard form, relatively unchanged from 1938. And in a time of even more rapid social and technological change than back then, he still has the potential to be extremely compelling. How can this be, you ask?

Well, he’s Superman, of course.

Next time: the Atom Age, Marvel’s First Family, and a new paradigm!