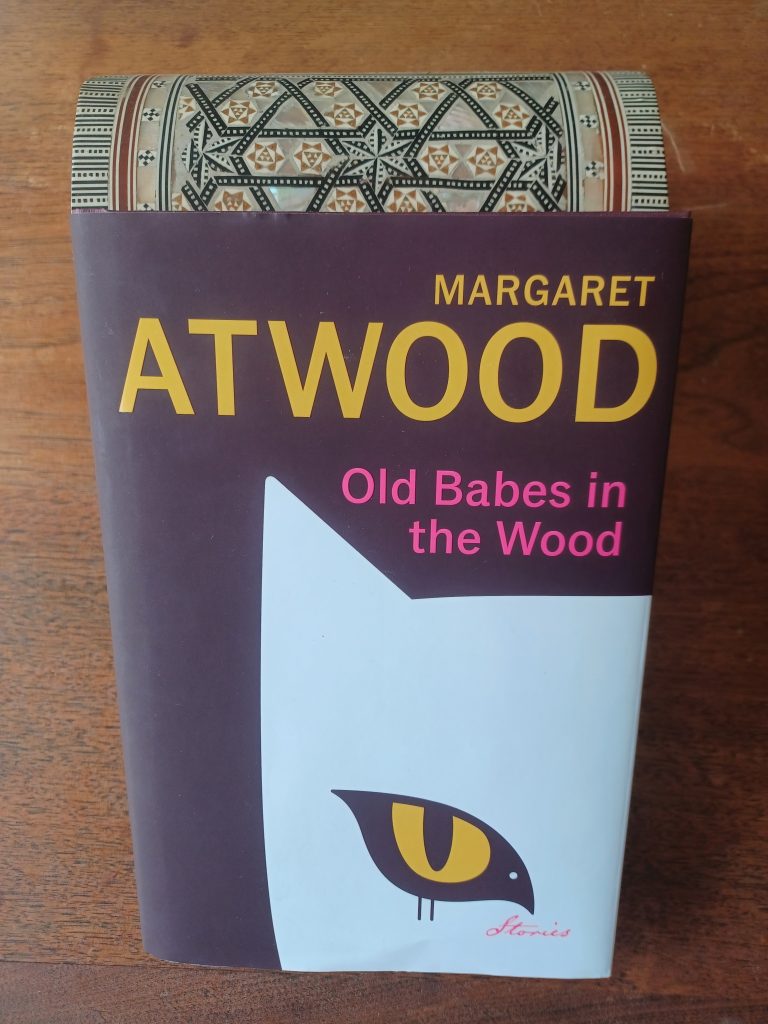

Old Babes in the Wood is yet another literary masterpiece by the great Margaret Atwood which covers the pandemic, grief, memory, the ever-fluctuating nature of language, witches, aliens, and most of all, death. From “Impatient Griselda,” a twisted fairy tale recounted by a cephalopod alien to a group of humans in quarantine, to “Old Babes in the Wood,” a poignant realistic story about returning to a family cottage after the loss of a loved one, Atwood has created a collection with something that will appeal to everyone who reads it.

I appreciate that in this collection, Atwood seamlessly includes stories from various genres side by side. While many authors separate their speculative fiction into individual collections, the diversity of genres in this collection made it better. All the stories work well together, and the mix of comedy and tragedy further reflects the complexities of life for the reader.

Old Babes in the Wood is bookended by a short story cycle, à la Alice Munro. The first and third sections revolve around the characters Tig and Nell, a married couple. Atwood peeks into their lives through the lens of memory, such as when Nell and Tig remember the stories they heard from an old French landlord. The death of a family cat results in a melodramatic but nonetheless emotionally poignant recollection of his life, and Nell memorializes Tig’s father as she sorts through his personal effects.

Although most of the stories are told through the retrospective view of a couple stepping into their twilight years, Atwood makes the stories feel alive and vivid. The connections of the memories to tangible objects and the descriptions of Nell and Tig’s house as it slowly fills up with the collections of their lives naturally draw readers in. Atwood has spent years refining her style, and her ability to create great, sweeping stories that focus on the minutiae of life is impressive. Atwood deftly establishes the characters and their relationships with only a few lines of dialogue, and her poignant emotional descriptions are the perfect match for it; she allows the reader to see how this life-long couple communicates, both verbally and silently. I was very moved by their stories, and frankly, I could have read an entire short story collection that simply follows their lives.

Old Babes in the Wood also contains individual short stories that have no relation to one another. These individual stories are framed through a tradition of storytelling and memory that allows the reader to imagine the worlds and rich lives of the characters outside of the glimpses provided through the stories. The recurring themes of memory and loss experienced as one gets older are broached in several of these stories, including the Nell and Tig sequences, “My Evil Mother,” a story about the decades-long evolution of a mother-daughter relationship; “Bad Teeth,” a discussion between two old friends; and “AirBorne: A Symposium,” a meeting between ageing female academics who are struggling to establish a chair for a female professor which will outlive them. Nell and Tig’s reappearance provides an excellent conclusion to the collection, and Atwood’s portrait of grief is so real that it will make your heart ache.

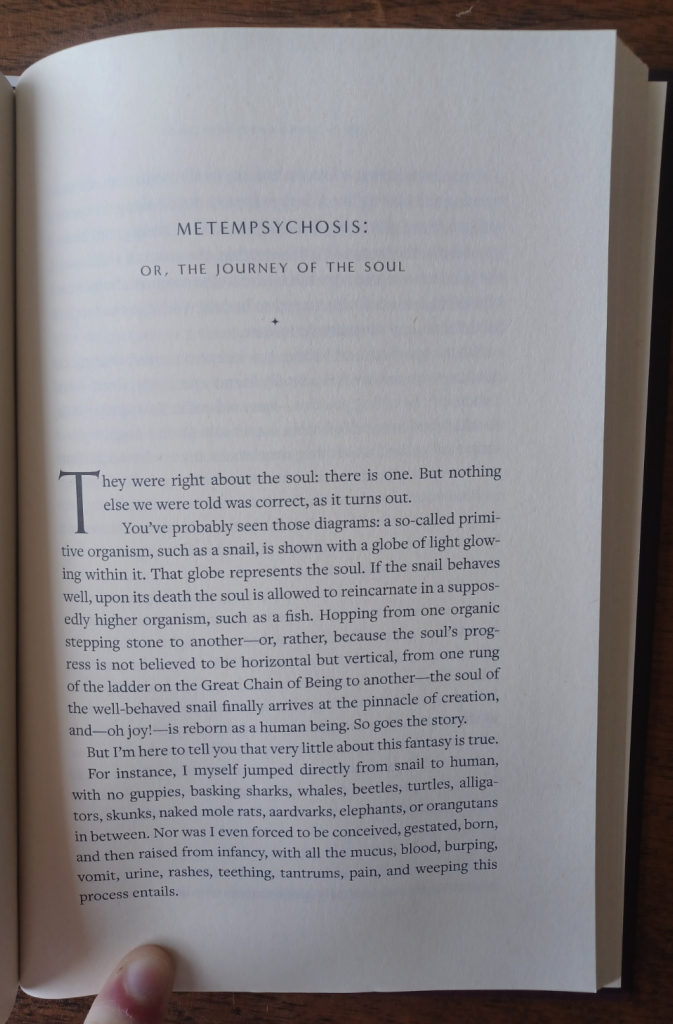

While I have great love for Nell and Tig, my favourite story from Old Babes in the Wood—which is on the shortlist for my favourite short story of all time—is “Metempsychosis: Or, the Journey of the Soul.” A Kafkaesque, fantastical exclusive of this collection, “Metempsychosis” follows the journey of a snail’s soul. However, when it is cruelly exterminated, it does not properly reincarnate in an infant state. Instead, the snail drifts into the body of a 24-year-old customer service worker, with the memories of its time as a mollusk fully intact. Confusion and chaos ensue—both for the snail and for the bank worker’s live-in boyfriend.

I have always enjoyed weird literature, and “Metempsychosis” is a perfect example of the genre. The snail never understands why it has to live in a human body—all it knows is the profound sense of wrongness that comes with such a drastic shift. The snail’s compassion for other small creatures offers a glimpse into a radically shifted world, in which appreciation of nature and one’s impact on the planet are at the forefront of human thought. The snail’s concern for what it consumes and how it can return to nature are portrayed in a compassionate and humorous manner. While the snail is clearly not human, Atwood does a great deal of work to anthropomorphize it and connect its beliefs to environmental philosophies that emphasize mindfulness, conservation, and respect towards lower life forms.

I also enjoyed how Atwood plays with gender in this story. As a hermaphroditic species, snails—as far as we know—do not have a conception of binary gender. Thus, when the snail is placed into the body of a cisgender woman, there is a fascinating sense of disconnect which parallels narratives of gender dysphoria. Gender remains an aspect of human society that the snail does not fully grasp; it is much more concerned with its physical body rather than the social aspects linked to it. Through this fascinating play with gender—and the fact that from an outside perspective, this story is about a woman experiencing some kind of break from reality—Atwood raises questions about gendered expectations of compassion and emotional labour.

Ultimately, “Metempsychosis” resonates with me most because of its compassionate portrayal of alienation. While there are comedic moments, the snail’s vastly different approach to life ultimately leads the mollusk to pure estrangement. This short story is a perfect example of how speculative fiction answers deep questions in weird and beautiful ways, and of the desire to slow down, which occurs across all species.

The slowing down of life is another theme in this collection. The majority of Atwood’s protagonists are getting into their twilight years, and have to reckon with both the loss of relationships and their physical ability. The story of this little snail reminds readers that slowing down isn’t just important for those leaving middle age; it is also for young people who risk burning out.

While a few of the short stories collected in this book, including the titular “Old Babes in the Wood” and “Impatient Griselda,” have been published individually, it is worth reading the book as a whole. This collection’s stories will profoundly affect you, and I was left thinking about them days later.