The Nature of Middle-earth, the first-ever publication of Tolkien’s final writings on Middle-earth, offers exciting new insights into the author’s genius but is not for the average Tolkien reader. Ever since HarperCollins announced this book back in June 2020, fans have been speculating about the contents of this book and how it would relate to previously published works.

Before going into details, some context is required. Since Tolkien’s death in 1973, his son Christopher Tolkien published volume after volume of his father’s legendarium until his own death in 2020. Most notably, he edited and published The Silmarillion, Unfinished Tales (UT), and the twelve-volume History of Middle-earth (HoMe).

Amazingly, even after all these posthumous publications, still more writings about Middle-earth remain. Carl F. Hostetter, one of the greatest living Tolkien scholars, worked closely with Christopher Tolkien to edit Tolkien’s linguistic writings. In The Nature of Middle-earth, Hostetter expertly compiles papers of a linguistic and theological nature, along with information about the flora, fauna, geography, and peoples of Middle-earth.

The book answers questions that have fuelled many debates within the Tolkien fandom, such as: who in the fellowship actually had facial hair? Did Gollum walk around naked? However, on the whole, this book will appeal most—as Hostetter himself says—to readers with a particular interest in UT and HoMe, specifically volumes X-XII. Not only is familiarity with these texts assumed, but these works are of a similar nature. So if you did not enjoy UT or HoMe because of the extensive notes and editorial commentary, then this book is definitely not for you.

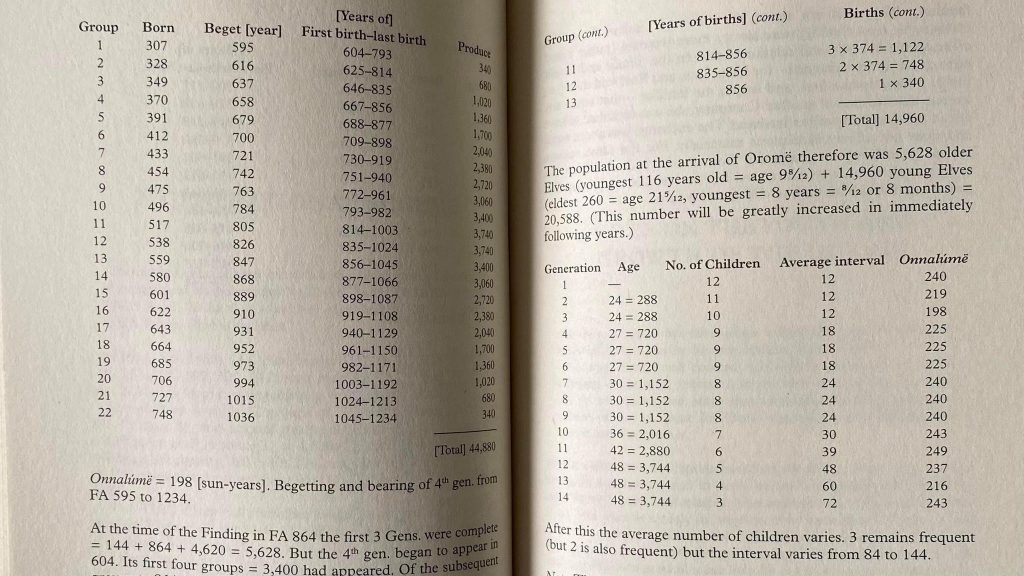

The book is divided into three parts. Part one, “Time and Ageing,” discusses the passage of time for Elves in Middle-earth through confusing tables and calculations, which I, unfortunately, did not fully understand. Tolkien also provides us with demographics concerning population growth and the ageing rates of Elves compared to Men.

Some of Tolkien’s tables and calculations published in The Nature of Middle-earth.

In the second part, “Body, Mind and Spirit,” Hostetter includes Tolkien’s writings on metaphysics, the relationship between the body and the soul, and how the Valar— the gods in the world of Middle-earth— interact with the peoples of Arda. While some of the information is convoluted, many details will be of particular interest to fanfiction writers, for example.

The third part, “The World, its Lands, and its Inhabitants,” includes a wide variety of subjects concerning the beings of Middle-earth and particular customs of the three races, such as Elvish economy, Númenórean marriage customs, and differences between Elvish dialects. As always, Elves get most of the attention, but there is some information about Dwarves. Since I am particularly fascinated by Dwarves, this part of the book was my favourite.

In an interview at this year’s Oxonmoot, Hostetter recommended starting with the forward, then reading the introduction to each part to gain a better idea of which sections of the book interest you the most. This is how I approached the book, and I wholeheartedly recommend it to everyone. The first part contained too much mathematics for my taste, so I started with the second part instead—and there is absolutely no harm in you doing the same. The book touches upon a wide variety of subjects, and you may still learn a lot from it even if you don’t read it in its entirety.

Moreover, as with the HoMe series, the editorial notes are crucial to understanding why the text is presented the way it is and even how seemingly unrelated writings fit together (some of the best information is in the footnotes, I can assure you). Again, it is essential to think of this book not as a novel that you read cover to cover but as a reference book or a FAQ for curious fans—something you can turn to when you have questions about Tolkien’s world-building.

Still, the book raises an important question: what is considered canon? Some of Tolkien’s writings included in The Nature of Middle-earth significantly alter what we know about his mythology. For example, in The Silmarillion, the sun was only created after the destruction of the Two Trees by Ungoliant—a spider even bigger and fouler than the one Frodo encounters in The Lord of the Rings. However, some writings published in Nature suggest that the sun was present from the beginning.

Some fans may find these inconsistencies irritating. Personally, I do not view these passages as inconsistencies, but rather as glimpses into Tolkien’s evolving conception of his legendarium. The scope of Tolkien’s writings and the amount of detail included in them equates him with writers such as Homer and Virgil. But seeing that he changed his mind and that he sometimes made mistakes makes him more human. Moreover, every fan has their own conception of what is canon, so if the information in this new book doesn’t appeal to you, you are free to ignore it. Tolkien’s changing vision only allows for even more interpretive liberty.

Some fans were concerned that this book was only a collection of notes found in Tolkien’s trash. Of course, Tolkien probably never intended to publish these writings in the form that we have them, but that doesn’t mean that they have no value. Carl F. Hostetter did a remarkable job compiling all these notes, and his introduction and notes are clear, insightful, and indispensable. Any Tolkien fan may be interested in obtaining this book to peruse through it from time to time, but for the Tolkien aficionados who love to dig through notes for hours, then The Nature of Middle-earth is a must, and it is ready to answer your burning questions.