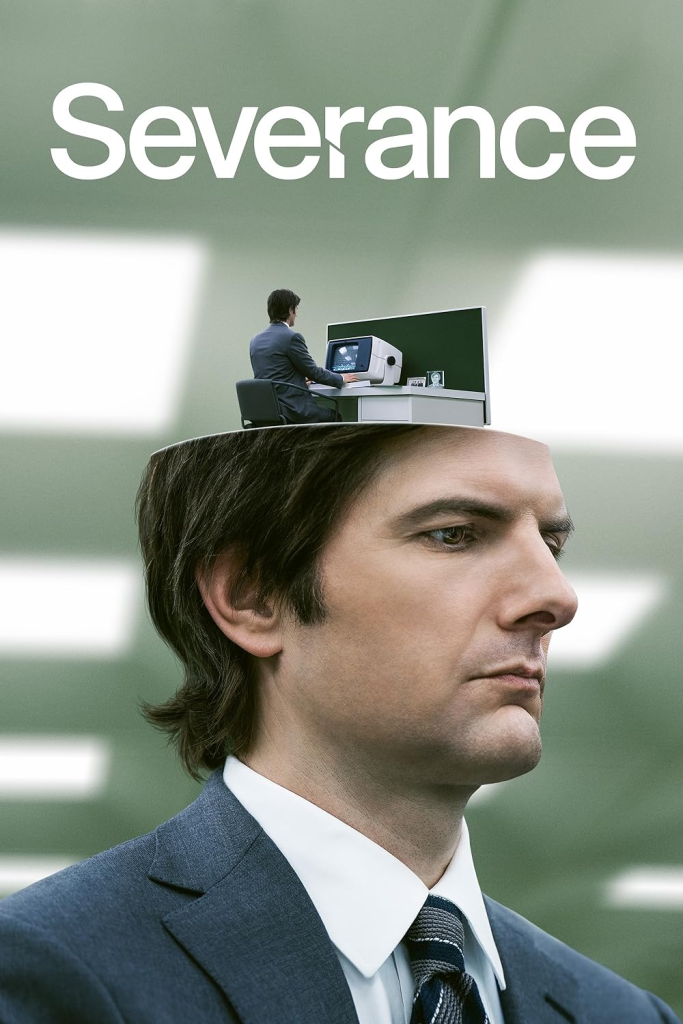

Apple TV’s Severance was released in 2022 to instant critical acclaim. The show follows Mark, an employee at Lumon Industries, who has undergone a procedure that separates his work life from his personal life. A chip installed in his brain is the trigger; when he gets on the elevator at work and descends to the “severed floor,” he forgets everything about his life outside of what he does in the office. When he leaves at the end of the day, the opposite occurs, and his external self has no idea what he spent the last eight hours doing. Part workplace comedy, part psychological horror, andpart sci-fi drama, Severance is disconnected from any one genre in the same way its characters exist in a state of alienation. Producer Ben Stiller said that the show is not exactly science fiction but closer to alternate history. Nonetheless, its speculative elements shine through and brilliantly strengthen a harrowing capitalist critique.

Severance’s approach to capitalism is ironic for a show produced by one of the biggest corporations in the world, but there is no denying its explicit Marxist themes. (For those who question if this is a valid interpretation, look no further than Mark’s employee name: Mark S., or MarkS, pronounced “Marx.”) Karl Marx’s writings define four dimensions of alienated labour, all of which are clearly expressed throughout the first season of Severance.

The first two features are related to production: alienation from the product the workers are creating, and alienation from the process of creation. These dimensions are the driving force of Severance’s plot: outside, Mark has no idea what he does at work and is desperate to figure it out. What he doesn’t know is that the Mark on the inside is just as blind. In the Macrodata Refinement (or MDR) department, where the main characters spend their day, employees sit at a computer and sort grids of numbers into different categories based on the emotion those numbers make them feel. What these numbers mean, why they invoke such visceral reactions, and what happens when they are sorted are all questions that remain unanswered. It isn’t until the MDR employees brave the stark white halls and travel to Optics and Design that they come across some of the items Lumon is producing: namely, a watering can and a series of bizarre instructional cards for how to fight. But even these appear intended for internal distribution, and everyone is left to wonder: what on earth is Lumon actually doing?

The next dimension is the motivating factor for most main characters: alienation from others. Any attempts by employees to connect are shut down by management. All departments are physically separated by maze-like hallways, and propagandistic tales are established within each department to dissuade interaction among employees. By a certain point, characters are literally locked into their office to prevent fraternization. Inside, Mark initially bought into the idyllic workplace Lumon was selling until his best friend Petey suddenly stopped showing up with no explanation. Mark tries to continue as usual, but Petey’s disappearance is the first sign of a crack in Lumon’s image amongst severed employees, and the catalyst that makes Mark question the reality of his existence on the severed floor. Other characters are just as motivated by their human connections: goody-two-shoes Irving starts to break the rules when he develops a fondness for Burt, and Dylan is never the same after an emergency protocol procedure reveals that his outside self has children. Because of their severed condition, employees are fully alienated from the outside world, allowing Lumon to define what “normal” workplace expectations are. This leaves them with no knowledge of the laws and organizations that could take action against their abusive management and, most importantly, no understanding of their position in society. It’s only when a piece of non-Lumon literature makes its way into the office—a cheesy self-help book—that characters are awakened by the attitudes and beliefs of people on the outside.

The final dimension is essential to the internal struggle of Severance’s main crew: alienation from human nature or the self. When employees first arrive on the severed floor, they wake up on top of a conference room table with no idea who they are or how they got there. They have no functioning free will—none of them asked to exist, and their existence depends entirely on their outside self choosing to clock in to work every day. This lack of autonomy is demonstrated on an existential level a few times throughout the show. Helly, desperate to leave, submits a resignation request to her outside self, which is rejected multiple times. She eventually receives a video response, saying, “I am a person. You are not. I make the decisions. You do not.” The total confirmation of her imprisonment and forced labour drives Helly to more extreme action. In another instance, Irving comes across a party for Burt, the head of Optics and Design. Employees watch a video from Burt’s outside self thanking his unknown coworkers for the years they spent together. That Burt then states that he will be retiring. A small celebration occurs, but there is a dark cloud over the whole event. In a place like Lumon, where one version of a person only exists at work, retirement is equivalent to death.

Domineering, evil corporations are a classic sci-fi cliche. Blade Runner has the Tyrell Corporation, The Terminator has Cyberdyne, and The Fifth Element has Zorg Industries.

In many cases, these corporations are the villain because people know exactly what kind of evil they’re participating in. When there’s something more sinister under the surface, it’s usually uncovered by the protagonist in a grand reveal, like the now-famous spoiler from 1973’s Soylent Green: “Soylent Green is people!” The story of Severance isn’t over yet (and surely more of Lumon’s secretive behaviour will come to light as the show progresses), but for the entire length of the bizarre first season, audiences are left with no single clarifying clue about the nature of the “mysterious and important” work taking place at Lumon. This pushes the focus of the plot away from Lumon and towards the people it affects, bringing important real-world insight: regardless of what kind of labour we are forced to perform in a capitalist system, it can alienate us from creating meaningful relationships with ourselves and others.

And we don’t even have chips in our brains.