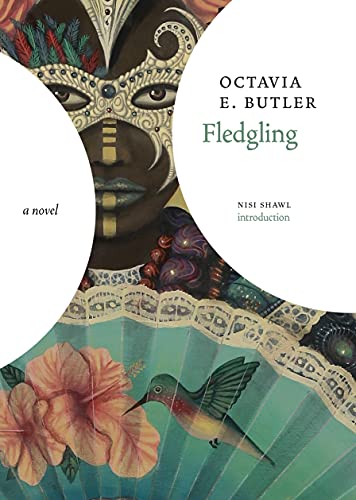

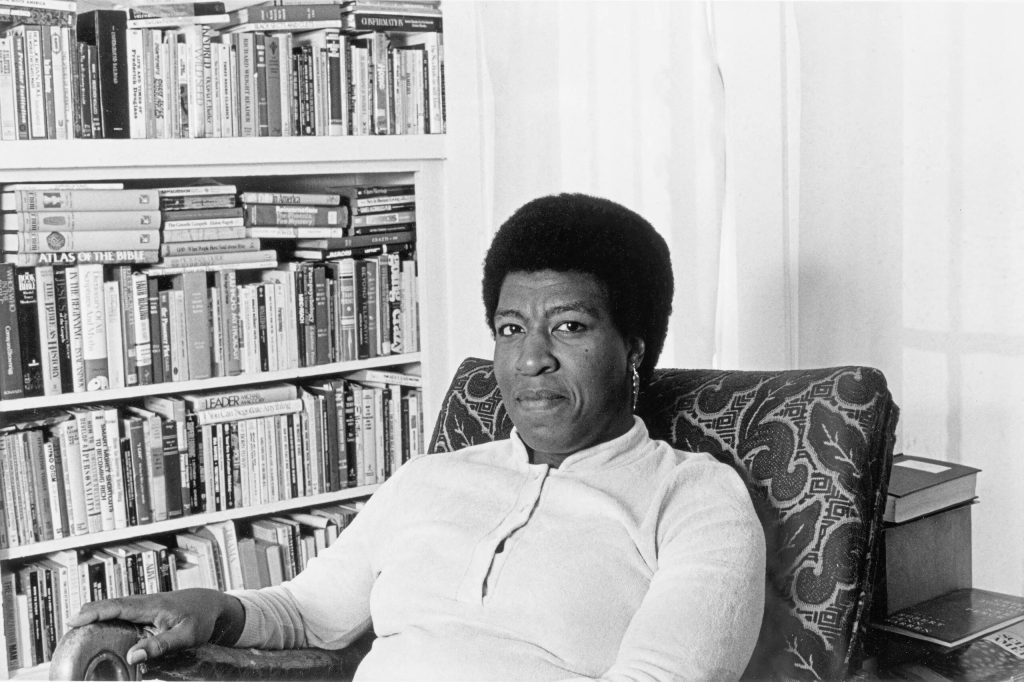

Vampires are a cultural staple. From Dracula to Twilight, they have found their way into much of our popular media. But no interpretation has ever felt quite so unique or fresh to me as Fledgling’s Ina, a vampiric race of people living alongside humanity, albeit governed by their own unique rules and customs. This re-interpretation of a much-loved folkloric creature is what initially drew me to Fledgling, yet it is the discussions the novel has around mutual need and navigating a world hostile to your existence that cements it as an underlooked gem in science fiction. In her last novel, Octavia E. Butler fuses the supernatural with science fiction to explore themes of otherness and mutual dependency—a venture that, while somewhat difficult to parse, brings to the forefront many questions of how science fiction can be used to explore complex interpersonal relationships.

The novel centres on Shori, an amnesiac girl who discovers she is a 53-year-old vampire, genetically spliced with human DNA, which allows her to walk in the sun. Depending on who you ask, Shori is either a threat to the Ina way of life or the next step in their evolution. Butler, famous for using her science fiction novels to explore the complex identities of Black women, uses this concept of dual perspectives to explore what it means to be Other and how humans relate to that which is different.

Fledgling explores the theme of otherness in two ways: through Shori’s interplay with the Inas she meets and her bond with her Symbionts, the humans she feeds on for nourishment. Shori is an anomaly of an Ina, the product of a genetic experiment that, while successful in its aims to reduce the Ina’s susceptibility to the sun, has made her distinctly different from the rest of her people. She is the first black Ina, thus forcing the Ina to decide what it means to be Black in their society for the first time. As a naturally pale people who have never really considered race the same way humanity does, they are split on the implications of being both an Ina and Black. Shori is thus an outsider in both the human and the Ina worlds, a person who has to prove her value time and time again. The internal conflict of the Ina underscores this: they are unsure what it means to be different and yet unmistakably an Ina. Thus, Butler questions what it means to be Other—to not fit into the societal model.

“‘I don’t think I’m supposed to be alone,’ I said. ‘I don’t know who I should be with, though, because I can’t remember ever having been with anyone.’”

Fledgling, p. 26

The inclusion of human characters strengthens the themes of otherness further. The relationship between the Ina and their Symbionts is perhaps the most compelling aspect of Fledgling— a relationship which, as the name implies, is supposed to be mutual. The Ina need sustenance from humans, and the human Symbionts live longer, healthier lives thanks to the Ina venom injected with each bite. The bond between a human and their Ina is not always perfectly equal, however. Humans find themselves under the thrall of an Ina, unable to be apart for too long or disobey their master’s orders. Throughout the novel, Shori tries to strike a balance in her relationships with her Symbionts—especially when it comes to her first and primary love interest, Wright—and avoid taking too much of their autonomy. Butler mirrors his push and pull of mutual need and uncertainty across other prominent Inas in the novel, showing how complex these relationships between somewhat unequal partners can be. All of these nuances in the Ina-Symbiont relationship work to further what Butler explores with Fledgling: how do we relate to those so wildly different from us? She doesn’t offer any easy answers here; instead, it is the messiness and the confusion of the majority of the characters that Butler highlights.

For all its deep theming, Fledgling can be a difficult novel to enjoy. Despite its fresh take on the supernatural and science-fiction genres it’s playing with, it can be an uncomfortable read, especially regarding the romance, which sometimes blurs the lines of consent, as Wright is incapable of disobeying his Ina. Furthermore, Shori, as a young Ina, is at once an adult and child, a concept that is not always tackled with the delicacy it deserves. Compared to other novels by Butler, such as the phenomenal Parable of the Sower, Fledgling is harder to connect with and more abstract in its perspectives and content. While I believe the novel is a great experiment in playing with genre and re-interpreting vampires to prompt new conversations with some fantastic worldbuilding at its core, the characters and their messy relationships make it difficult to love and impossible to recommend without a disclaimer or two.

Regardless, Fledgling has a lot of interesting things to say. It is perhaps not a novel for everyone, and I don’t unambiguously love it, but it still manages to play to its strengths well. Butler’s take on vampires, their desires, and how a parallel but different race of humanoids would interact with our world is compelling and certainly the most unique and refreshing I’ve ever encountered. Under Butler’s vision, vampires become a unique people with their own cultural and linguistic traditions. Thus, while I wouldn’t necessarily recommend Fledgling as it is difficult to parse at times, with dense swaths of exposition and complex, uncomfortable relationships at its core, it still manages to say some insightful things about humanity.