By Olivia Shan

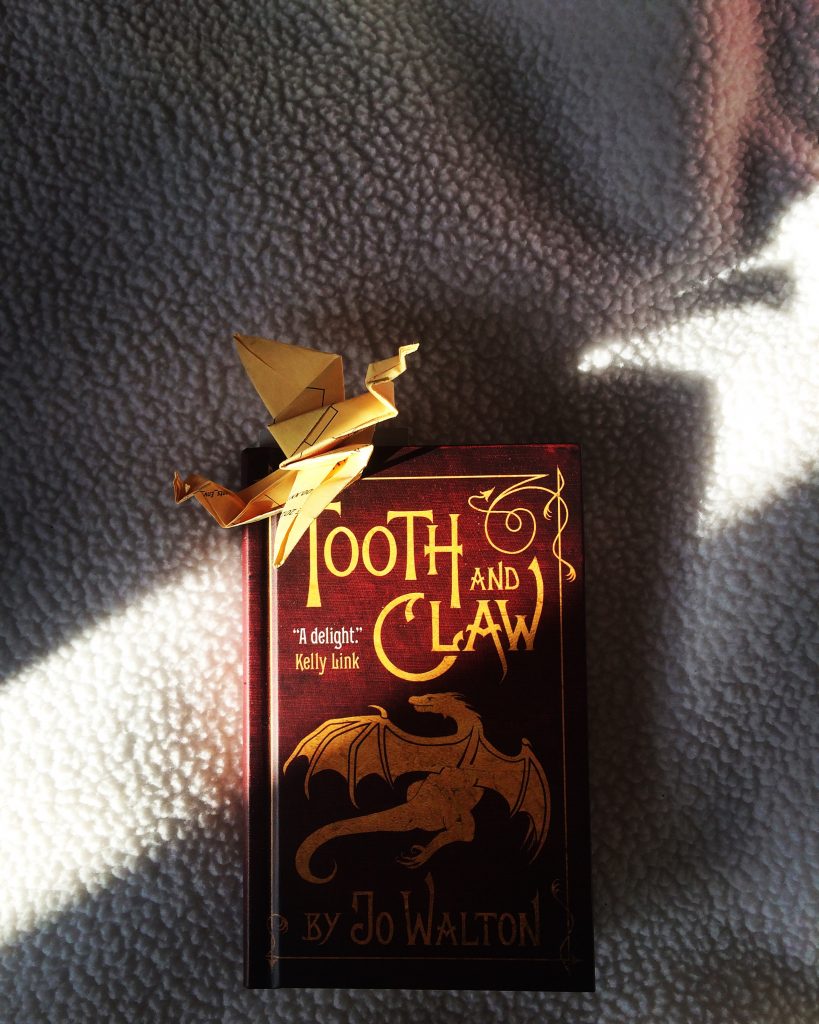

I can hardly remember the last time where I was so enticed to pick up a book just to be able to confirm whether or not it measures up to its own irresistible premise. In Jo Walton’s 2003 novel, Tooth and Claw, the celebrated fantasy author reimagines an alternate version of 19th century England where the world is now run by a society of anthropomorphic dragons who nonetheless still live by the moral and social standards of a Victorian era novel. However unconventional the synopsis might sound, the story itself begins in a rather quintessential Victorian way; we follow the death of a rich family’s patriarch and the inevitable bickering that ensues over the much sought-after inheritance. Of course, in this world, the patriarch is a 300-year-old dragon and the inheritance in question is none other than his own seventy feet long body.

Indeed, in the world of Tooth and Claw, a death in the family isn’t only a time for grief and mourning, it’s also the occasion to feast on said family member’s remains. Cannibalism is more than just a normalized custom, it also represents a special physiological need for the dragons; consuming the flesh of a fellow dragon—especially one that is particularly large and strong—heals, restores, and allows one to take a part of their strength. Therefore the body of a loved one isn’t only a precious inheritance meant to be left for younger dragons, it is its own complicated form of wealth, of power, of food. In a very literal sense, one’s family is a resource.

Just from that explanation alone, one can tell that Walton is really swinging for the fences here. It’s fascinating to read about all the ways in which the classical elements of 19th century fiction can be melded together with intense dragon lore and mythology. This intertwining of different worlds is a literary act which is difficult to pull off, and a less talented writer could have easily made the book’s contrivance seem cheap and gimmicky. Luckily, Walton is a bold, assertive writer and possesses a wealth of creativity. From the very first chapters, you know that you are in the hands of someone poised, conscientious, and tremendously skilled. There is no need to be intimidated by the slightly archaic writing style because the author doesn’t ever take your attention for granted. You can trust her to take you down the path of this endlessly entertaining romp of a book without stumbling onto any major bumps along the way.

More than anything, this novel is an incredible display of Walton’s world-building skills. I found myself consistently enthralled whenever she described another detail or ritual in which these dragons partake however weird they may be. Small things like walking to a location as opposed to flying there have vast implications. As a matter of fact, nearly everything— down to the kinds of hats or wigs they wear to court— has its own little, but not too little, implication. Miraculously, nothing ever strays too far into the ridiculous which is largely a credit to the author’s confident storytelling, but also, these aren’t just wacky, random indulgences parsed throughout a narrative. Every behavior and every ritual dovetail into one another in a surprisingly cohesive way. They feel undeniably believable within the context of the world, and one comes to realize that the tongue-in-cheek silliness is just part of the fun of reading Walton in the first place.

Alternatively, the satirical vein that runs throughout this novel is, like everything else, clever and effective. The contradictory nature between the gruesomeness of the dragons and their dogmatic, self-regimented respectability is rendered spectacularly well. Scenes where characters are discussing the technicalities of a lawsuit or the suitability of somebody else’s estate while ripping apart raw meat literalizes all of these characters’ inner hypocrisy. As Tooth and Claw is reflective of both high Victorian novels and Victorian romances, Walton brilliantly translates the implicit paradoxical situations faced by those archetypal characters into her own work. In fact, she raises the stakes even further by materializing them into her characters’ visceral physiology. Consequently, the less fortunate dragons of this world— women without secure social positions, weak and sickly children, paupers—are not only the inevitable victims of a system which leaves them vulnerable to exploitation and abuse; they are often just outright devoured by the more privileged members of society: a statement on Victorian England’s metaphorical consumption of the vulnerable.

Additionally, the fraught social position of women, the topic of many Victorian romances, is also amply explored in fascinating ways, particularly pertaining to the subjects of romance and courtship. The sole purpose of the impossibly delicate, powerless, fainting young women of that literary genre isn’t only to find themselves a good, respectable match, they are also expected to do so without so much as having a full-fledged conversation with their prospective spouse, let alone expressing any type of intimacy or affection. Being a female is even more of an ordeal when one is a character in Walton’s Tooth and Claw. In fact, young women must avoid interacting with any members of the opposite sex with whom they are not related, as just being in close proximity with a male can cause their golden scales to blush into a permanent pink, effectively signaling to the whole world their “naughty” behaviour. Hence, in Walton’s Victorian-dragon literary mash-up, to breach any of society’s implicit rules is not only to be subjected to shame and judgement, it’s to be downright humiliated and exposed, with a threat to your own life hanging in the balance. A book which manages to explore all of these complicated nuances succeeds in making even a familiar story feel exciting, rich, and alive.

Whether you like dragons, Victorian novels, or neither, there are elements about this book that are going to delight every kind of reader. Tooth and Claw is a book that works on multiple levels; it’s a weird and refreshing take on a fantasy, a wildly entertaining family drama, a poignant yet hilarious satire, a tender story of love and duty, and—above all—an unequivocally fun novel. It’s also a special experience to read a book where you can very clearly tell how much of a good time the author herself had writing it. That pure joy and enthusiasm certainly comes through in every page. This novel is a great example of the kind of finely crafted escapism which many of us might yearn for during these long and difficult times.