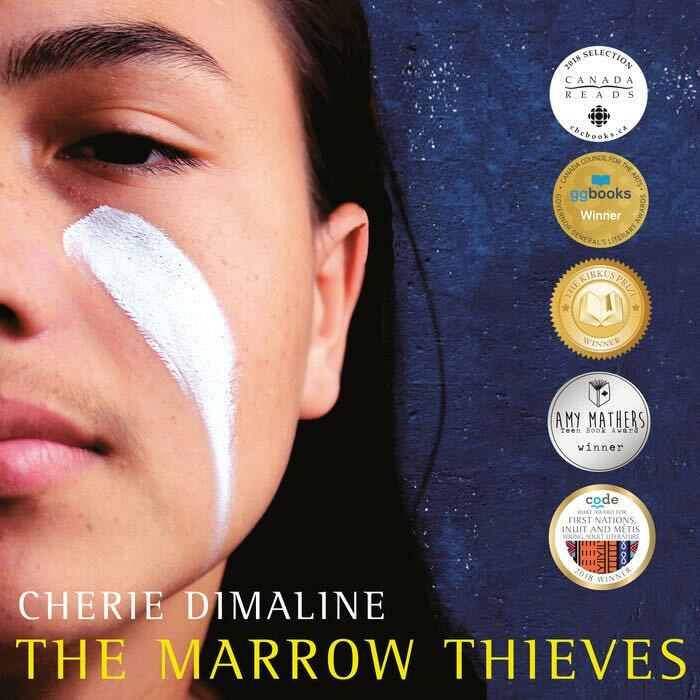

Truthful storytelling is integral to the discourse of Canadian reconciliation. What scars are hidden behind our narratives of history? What roots do our views have in colonialism? Métis author Cherie Dimaline’s dystopian novel, The Marrow Thieves, winner of the 2017 Governor General’s Award for English-language children’s literature, brings readers into a post-apocalyptic future to interrogate the North American past and present, with the help of a fresh perspective.

In this version of history, climate change’s last gasp has incapacitated the world through a deadly epidemic. When Indigenous peoples are discovered to be immune from the illness, it triggers a genocidal hunt to extract a cure from bone marrow. Dimaline takes us through the eyes of a young boy, Frenchie, after his last remaining family member is taken away. Alongside a band of fellow runaways, Frenchie survives in the Canadian wilderness with renewed stories of the past and a childlike hope for the future. As a powerful form of resistance, the future setting of the novel affirms that Indigenous communities have persisted through history; they will survive beyond this crisis and the next.

The Marrow Thieves explicitly contests the false representations of Indigenous peoples which fill Western narratives of history. Ethnic cleansing schemes, such as the Sixties Scoop and residential schooling, operated under the absurd notion that Indigenous people were inherently unfit to raise their children. In The Marrow Thieves, a found family of five orphaned children is protected, taught, and loved by two Native elders simply based on the principle of community. This group travels together despite the elders’ slowness and small children’s vulnerability, because collective care is fundamental to their identities. Dimaline rejects stereotypes by presenting a cast of characters who plan, organize, and fight their way to freedom while consistently upholding their Indigenous identities.

Ironically, in modern history, famous stereotypes surrounding Indigenous cultures and histories are often kept alive by children’s literature and popular culture. Countless works of the genre reenact the fables of colonialism through a thick, tinted lens, from the dubious romance of Pocahontas, the violent representation of a tribe in Peter Pan, to the alleged harvest celebrations between pilgrims and Natives we recall every autumn. These stories, while seemingly grounded in fact, are as whitewashed and fantastical as the Grimms’ fairy tales. Ultimately, when children rehearse these false narratives of colonialism, accept them as truth, and carry them into the future, it only inspires the survival of an imperialist regime . This long-held function of children’s literature intensifies the value of Dimaline’s YA resistance piece, where truthful storytelling becomes the key to saving the world.

In two chapters, titled “Story,” Miigwans, the group’s male elder summarizes Canada’s history from the origins of the Anishnaabe to the novel’s extrapolated eco-apocalypse. Frenchie notes that, in the style of oral tradition, Story shifts in length and focus with each retelling. Occasionally, Story expounds on the history of treaties. Other times, it includes an account of earthquakes that prompted the apocalypse. In every case, Story illustrates a centuries-long exploitation of Indigenous peoples which results in exile, loss of culture, and death. In contrast to the distortions of modern children’s literature, Frenchie and the family choose to withhold Story from the youngest child until a certain age, so she can “form into a real human before she understood that some saw her as little more than a crop.” Dimaline’s Story thus illustrates the mechanism of cumulative, post-colonial trauma with careful consideration of its weight.

Further, Dimaline uses Story to comment on commonly overlooked phenomena like New Age cultural appropriation and active exploitation of land and resources during the days of “reconciliation.” Miigwans describes the attitude of Canadians at the start of the epidemic, saying, “They asked to come to ceremony. They humbled themselves when we refused. And then they changed on us, […] looking for ways they could take what we had and administer it themselves. How could they best appropriate the uncanny ability we kept to dream?” For Indigenous communities, colonization is, and has always been, more than the theft of land; it includes the destruction of nature, partition of communities, commodification of culture, and financial exploitation as well.

In the end, it is this act of painstaking cultural preservation which saves the found family from destruction. The marrow thieves are wrecked by a final act of resistance by the second elder of the family, Minerva, the only one left who can fluently speak an Indigenous language. Dimaline treats language as a tangible weapon her characters can use to save themselves and one another. Indigenous culture physically empowers its native bearers with community, resilience, and the ability to dream. Authentic storytelling in Canadian children’s literature is crucial to our future as a country. The violence of history is, undoubtedly, a heavy burden to carry. But The Marrow Thieves succeeds as a young adult novel by drawing a future where community, imagination, and cultural preservation are powerful enough to beat even the darkest evils.