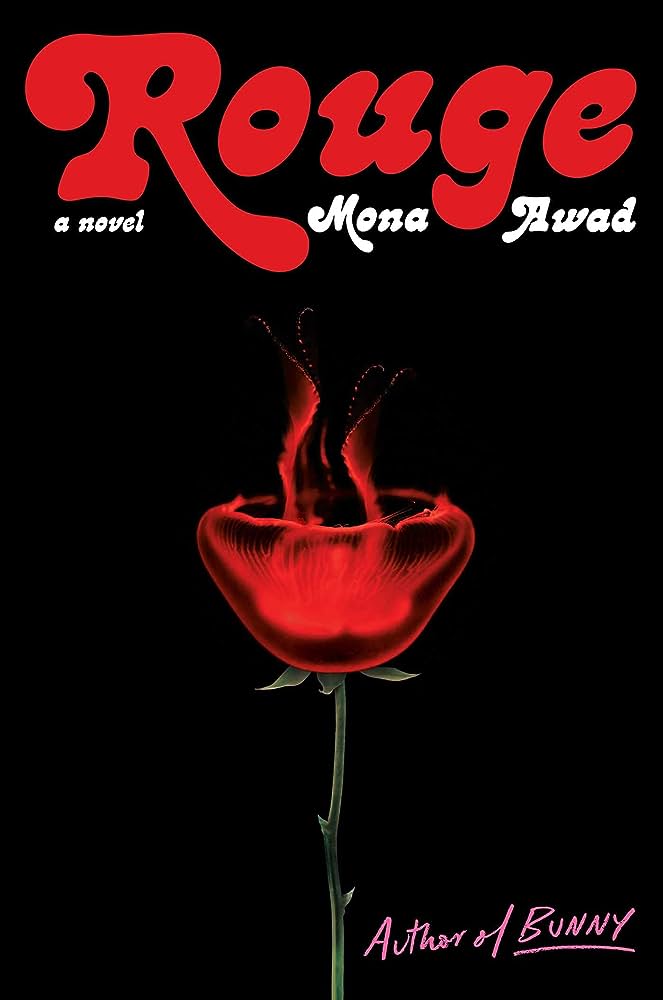

As a chill floods the air and the leaves begin to crisp, Mona Awad returns to shelves with a gothic novel chronicling the horrors of the beauty industry. With Rouge, the author of recent BookTok sensation Bunny takes the reader through the eyes of Mirabelle Nour, a French-Canadian and Egyptian woman grappling with grief, obsession, and a rapid rise up the ranks of the novel’s eponymous prestige skincare company. In an attempt to investigate her mother’s involvement with Rouge, Mirabelle falls progressively deeper into the madness of perfectionism.

Rouge offers its members the chance to become their “Most Magnificent Selves.” With enough masks, massages, and money, “candidates” hope to cause delirious envy from all those around them. With every treatment, members leave brighter and lighter in mind, body, and spirit. Side effects only seem to include strange slips of the tongue and great lapses in memory. Over time, these losses compound to “miraculous” ends.

Revealed through a series of flashbacks, many of Mirabelle’s repressed traumatic childhood memories are unearthed during her treatments at Rouge. Awad grounds the novel in these scenes, allowing the reader a beacon of humanity in a narrative voice otherwise fixated with self-obsession. In a schoolyard game, Mirabelle sits neatly within a circle of girls, each raising their hands to label one another as pretty or ugly. Mirabelle receives no votes for the former. Awad illustrates this experience with the exact bitterness you would expect and positions it perfectly to highlight the major impact childhood has on one’s sense of self. Unfortunately, this is where the roses for Rouge start and stop.

The criticism of beauty standards and the commodification of womanhood have become pervasive among Gen-Z women. TikTok’s devouring of the male gaze theory and its ultimate “female gaze” counter-reaction reflect a prominent— albeit surface-level— evaluation of the aesthetic expectations placed on women. The average literary fiction reader is, therefore, no stranger to the questions Awad poses.

“There is a whiteness, isn’t there? I whispered. Brightness, I meant to say. Not a whiteness, I told myself, call it a Brightness.”

Mirabelle has yearned for brighter, whiter skin since she was a child. With no access to her Egyptian family, she internalizes her physical difference from her French-Canadian mother as a glaring deficit. Especially amongst women of colour, eurocentricity in beauty is endemic. Awad spends hundreds of pages hammering this point in. Fair skin is, as expected, venerated as an ultimate target of a skincare regimen. Naturally, the beauty industry invents insecurities and sells them back to us in pretty glass jars, syringes, and lasers. But every trip to Rouge and every scene outside of it is flooded with constant pokes and jabs at the capitalistic evil of the industry. These points, without further development, sadly lack the nuance necessary to provoke thought in an audience all too familiar with these themes. Awad fails to extend her observations into meaningful commentary for the countless readers who have been in Mirabelle’s place.

Alongside Awad’s established body of work, Rouge is uniquely unrefined. Bunny finds its strength in Awad’s expert finesse in plot, character, and narrative voice. The speculative elements build gradually, toeing the line between fantasy and reality until a head literally bursts. Awad’s 2022 release, All’s Well, exhibits a similar level of precision and control. In her finest prose yet, Awad weaves an effective analysis of ableism through her protagonist’s Shakespearean experience of illness. Rouge fails to afford its reader the same breadth for interpretation as its predecessors. Its messaging is unsubtle to the detriment of each element of the narrative. There is no sense of intrigue despite the Wonderlandian, mysterious setting. There is no complexity to Mirabelle, used simply as a mouthpiece for female insecurity and desire. Further, the plot is congested with gaps and holes left by unfinished metaphors and throwaway characters, all reaching for the same ideas. In the end, Rouge is disenchanting; a chaotic, repetitive turn at cultural criticism that lacks every strength we’ve come to expect from the queen of Weird Horror.