Second part of a new series exploring comics history from the 1930s to the present by considering crucial works from each period. Whether a comic-shop virgin or an obsessive collector, you’re sure to learn something new and surprising!

America was in the grip of a new religion after World War II, the semi-divine spectacle of Hiroshima and Nagasaki having made all of Modern Man’s previous wonders pale in comparison. With the advent of the Bomb and the defeat of the Axis came a realignment of the popular consciousness: the gods and mythic heroes so beloved of fascism found themselves sidelined once more, beaten at their own game by a chillingly immediate alternative—the Almighty Atom. Suddenly all the drive-in horror films swapped out ancient vampires and reincarnated mummies for radiation-mutated animals and monsters freed by nuclear tests. Government science funding, eager to compete with the mighty Soviet machine, skyrocketed while nuclear drills became commonplace in schools throughout North America. Science, and by extension, reality itself, had become strange and terrifying almost overnight.

So where did that leave superheroes? After the Superman-led boom in the late thirties, which persisted throughout the war years, sales rapidly declined after V-J day. Most superhero titles were cancelled or re-angled to feature horror, Western, or romance stories. Even Joe Simon and Jack Kirby, co-creators of Captain America, bowed to the zeitgeist by branching out with Young Romance, generally considered the archetype of the ‘50s romance comic. The industry was dealt a further blow by the release of psychiatrist Fredric Wertham’s 1954 book Seduction of the Innocent, which tied comics to juvenile delinquency. Suddenly the unrepentant killing of criminals and gritty storylines that characterized the Golden Age were a no-go. Superheroes, as much subject to natural selection as any other beings, were forced to adapt.

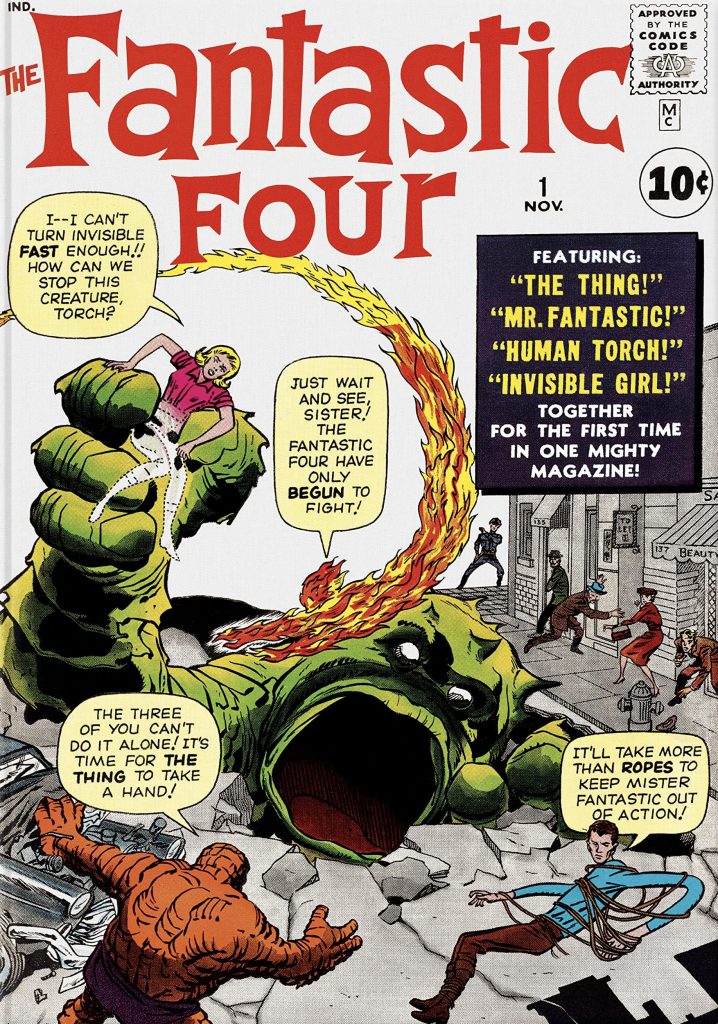

Enter the Fantastic Four, debuting out of nowhere in their self-titled comic, the cover of which displays a hyperbolic roll call: “‘THE THING!’ ‘MR. FANTASTIC!’ ‘HUMAN TORCH!’ ‘INVISIBLE GIRL!’ TOGETHER FOR THE FIRST TIME IN ONE MIGHTY MAGAZINE!” The irony, of course, is that none of these characters had ever appeared in any other magazines before. They would not have looked much like superheroes to the average reader accustomed to the Superman cape-and-tights model, either; all four are dressed in civilian clothes and display idiosyncratic, perhaps even grotesque, powers that mutate their bodies. The Thing, seen from behind, barely seems human (though his skin eerily recalls nuclear burn scarring), Invisible Woman’s body seems to be half-consumed by oblivion, Mister Fantastic’s contorting limbs never cease to look freaky, and the Human Torch is quite distinct from his Golden Age counterpart, who was usually drawn as a red man bathed in flame rather than the vaguely anthropomorphic pillar of fire seen here.

Despite all that, it was obvious from the cover and the issue’s contents that these were superheroes—a new breed, purpose-built for a new time. DC had also found success in the early 60s by revamping old myth-themed characters like the Flash and Green Lantern with sleeker looks and science fiction backstories, eventually pulling them together with Golden Age survivors Batman, Superman, and Wonder Woman into the astonishingly successful team-up title Justice League of America. But the Fantastic Four—even though the JLA’s success prompted their creation—were different. In their irresistible strangeness (much like Superman’s two decades before), they expanded the idea of the superhero, opening the floodgates for characters that deviated from the classic model, from the monstrous Hulk to the otherworldly Captain Atom to the deranged Creeper.

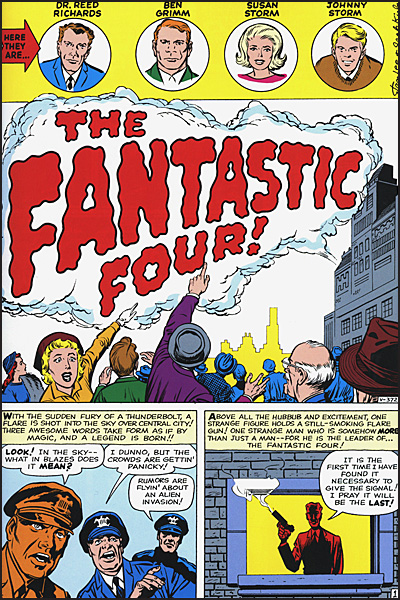

The story itself, despite the straightforward title “The Fantastic Four Meet the Mole Man,” plays with the mould of the standard superhero origin. Rather than economically summarizing the heroes’ backstory in the first few pages, like Action Comics, the issue opens in medias res with a silhouetted Reed Richards sending off a flare summoning the other Four, musing, “IT IS THE FIRST TIME I HAVE FOUND IT NECESSARY TO GIVE THE SIGNAL! I PRAY IT WILL BE THE LAST!” This is not the Golden Age hero leaping straight from a tragic backstory to an enthusiastic crimefighting campaign. Clearly, the last thing this Fantastic Four wants is to fight evil, but they are cursed to do so by their unique abilities. This plight alone already makes them more sympathetic than their precursors.

A flashback shows how they acquired them in detail, following the period’s ‘freak science accident’ trend. Their reaction to their bodily changes (caused by cosmic rays) is surprisingly human, quite unlike the perpetually unfazed demigods of the ‘40s: seeing his comrades, Johnny wails, ‘YOU’VE TURNED INTO MONSTERS… BOTH OF YOU!!” just before he bursts into flame himself. The profound identification is almost involuntary—we immediately realize these heroes are, in fact, people just like us. People thrust into an extraordinary situation, but people nonetheless, eminently relatable in their faults and struggles.

Of course, no modern reader would call Stan Lee’s punny dialogue realistic, nor is Jack Kirby’s legendary art designed to evoke verisimilitude. But together (a true collaboration, since the ‘Marvel Method’ had the artist share plotting duties), they achieve something truly unlike anything that had gone before. They brought the 20th-century wonder of superheroes into the Atomic Age—and not only by swapping out ancient gods for cosmic rays and nuclear power stations for bank vaults. The crucial substitution is of the archetypal peerless champion (embodied by Superman, Samson, Gilgamesh, and myriad others) for the everyman changed by forces beyond his control into something extraordinary. Lee and Kirby would develop this to its logical extreme (finding even greater success) in X-Men, where the superpowered mutants just happen to be born as members of a genetic minority.

For the denizens of a world where even the everyday suddenly seemed unfamiliar and potentially dangerous, this kind of hero struck a chord. Thus the industry force of Marvel was born, soon growing to challenge DC, which had reigned supreme since overtaking Fawcett thanks in part to a controversial court case. The established publisher would soon try to emulate Marvel’s humanistic style, with mixed results, but in time it became unthinkable to return to the functional dialogue and cardboard characterization that had served the medium’s infancy so well, just as the non-costumed pulp heroes became quaint with the coming of the Man of Steel.

A paradigm shift had come about—all thanks to the Four, still possibly the greatest (and most human) family in superhero comics.