By Francesca Robitaille

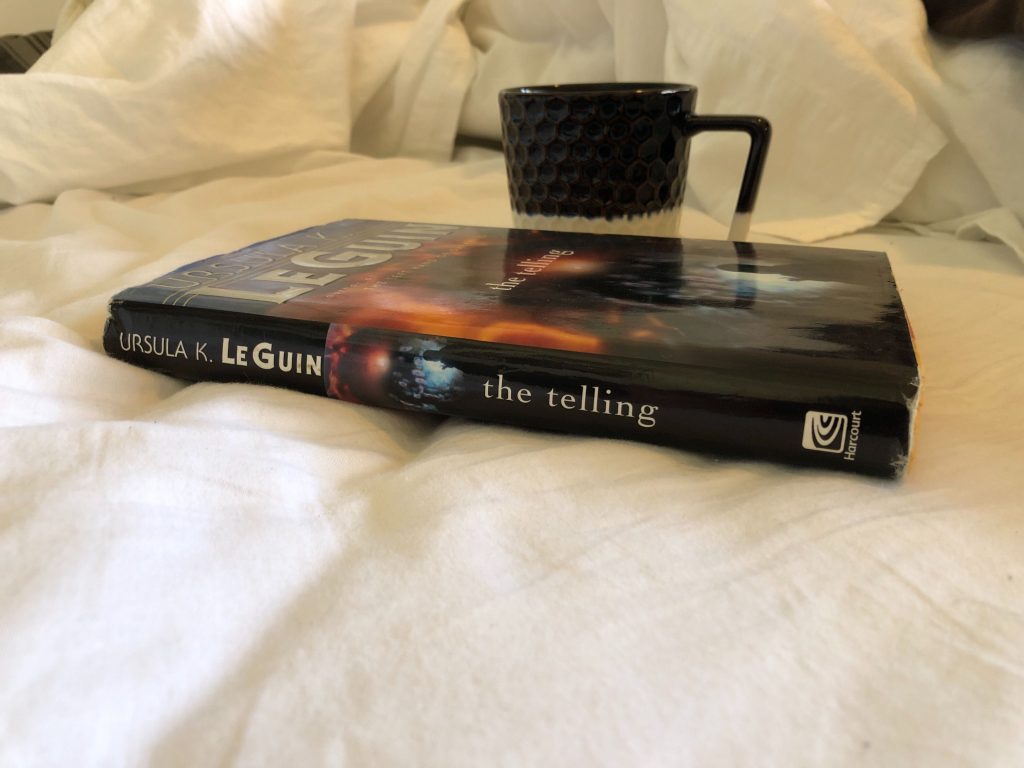

The Telling is one of the many novels making up the Hainish Cycle, Ursula Le Guin’s best known science-fiction series. Lesser known than some of its counterparts, it has only recently been taken out of print, although it can still be found via some second-hand booksellers – for now. Taking place on the planet Aka, a single continent world which has recently chosen to join the Ekumen, the society has shifted dramatically in a short time period. Sutty, the Ekumenical Observer, arrives on a planet nothing like the one her studies on Hain had taught her to expect, as the shift on Aka has been completed in the 70 years that passed on the planet during the time it took for her to travel from Earth.

As the narrator, Sutty’s point of view is tainted by her unpleasant experiences with the religious totalitarianism she lived through growing up. The Unists, a group of Christian Fathers, dominate Earth’s politics and are supported by terrorists launching bombs at learning institutions. She arrives on Aka to find that the world she studied no longer exists. A totalitarian, secularist government – different from the one she knew on Earth yet familiar in its attitudes – has taken over and imposed a language to be spoken by all, and any instances of the religious and cultural symbols of old are banned, something Sutty finds deeply upsetting due to her previous experience. Technological advancements for the planet must be purchased from the state-run Corporation, and are recorded via the ZIL, a sort of credit card-ID badge hybrid. Sutty feels lost, as everything she had hoped to discover and learn seems to be gone, replaced with experiences she had hoped to escape.

Following this 1984-esque introduction to Aka, Sutty receives permission to visit Okzat-Ozkat where she is introduced to the hidden element of Aka’s lost culture: the Telling. For the population of Aka, prior to the arrival of the Ekumen and the takeover of the state, the Telling was both the education and the religion of the people. Sutty is a welcome guest and eventually invited to travel with a small group to the Lap of Silong, the last place where the books of the Telling are being collected and hidden. The monitor, a government official who is vehemently opposed to Sutty leaving the capital, has tracked her location because of his deep-rooted belief that the state is correct to eradicate all traces of the old cultures. Sutty’s experiences on the Lap of Silong shake her beliefs and give her a better insight into the philosophy of the planet. She hopes to return to the capital and use her newfound understanding to build a bridge between the Ekumen and the people of Aka that allows each to talk to and learn from the other.

Like many of Le Guin’s works, this novel brings to the forefront the meeting and treatment of the Other, one with whom we are unfamiliar and to whom we are subsequently uncertain as to how to respond. The Hainish cycle serves as a beautiful reminder that listening to the Other and accepting the Other is vital to progress for both us and them. We may never fully understand the scope of the Other’s experience, yet common ground can be found to ensure both sides are better off through empathy and listening. The beauty of this theme can be found at the societal level in the conclusions Sutty proposes and in her personal experiences with the Monitor, an Other she does not treat with empathy until their fateful encounter in the mountains.

Something I find interesting because of my current life experiences, however, is the relevance of the monitor’s actions as a lone extremist attempting to take harmful actions against a peaceful group. How often have we heard a tragic end to that story in the news? I find the understanding and tolerance shown to the monitor in the rescuing and healing of his injuries by those he has hunted more telling. The maz (teachers of the Telling) permit him to go through the library and read parts of the Telling under supervision, in the hopes he might gain a better understanding and lose his extreme views through learning and tolerance. It gives me hope that eventually extremists can be converted to moderate viewpoints that, at the very least, do not disrespect anyone’s right to exist.

Another element of the story I found relevant to my experience is the ZIL. This card that shares your purchase and displacement history with the state is eerily reminiscent of discussions concerning the issues and lawsuits regarding the rights we have to our information and privacy that are controlled by largely unregulated technology giants such as Amazon, Facebook, and Alphabet (Google’s parent company). While the European Union has been taking steps to regulate them, with strong support from their constituents, North America has let them flourish in a market more reminiscent of the Wild West. However, as California has passed laws similar to those in Europe, there is the possibility that other states and Canada will follow suit, giving us better control over our own information and privacy.

However, if you have little to no interest in these topics, or if you were hoping for a break from the dystopian type of story, you will still likely enjoy this novel. The beauty of many of Le Guin’s stories, The Telling included, is that they can just as easily be read for pure enjoyment as they can for academic dissertation. While it is important to read for our education, individually and as a society, I have found the two – education and pleasure – to be tightly intertwined. I appreciate that as the reader, you can choose to take in the aspects of Mao’s China delicately woven into the story and the world built around it, and as well choose to read on for a more in-depth learning after finishing the book; alternatively, you can focus on the beauty of the story-telling in the novel, which is a part of the reading experience that is lighthearted and agreeable enough for anyone looking to escape a disheartening day. My favourite connection to the story was Sutty’s travels by boat to Okzat-Ozkat, and later on through the mountains. Le Guin uses a fluid and seamless writing style that transported me directly to the places I was reading about, complete with vivid imagery running through my mind. I am now inspired to cancel my summer internship and go off travelling for four months, which sounds great on paper but to which my student bank account says, I don’t think so. In The Telling, I am reminded of the beauty in storytelling. My biggest takeaway is a reminder that it is important to tell stories, listen to stories, and to not forget to live stories of our own.

Revision : Olivia Mendelson