Fourth part of a new series exploring comics history from the 1930s to the present by considering crucial works from each period. Whether a comic-shop virgin or an obsessive collector, you’re sure to learn something new and surprising!

As the century that birthed them drew to a close, superheroes found themselves somewhere they hadn’t been since their heyday during World War II: everywhere. The Tim Burton Batman films (and their distinctly inferior Joel Schumacher-helmed successors) re-established their credibility on the big screen after the Superman series’ descent into mediocrity. A collectors’ craze sent sales of the comics themselves—especially ‘special editions’ with tinfoil plating and #1s on their covers—skyrocketing. Everywhere you looked in the 1990s, superheroes were mainstream again. Rather than crumble in the revisionist glare of Watchmen and its fellows, the archetype had returned, true to form, revitalized and more powerful than ever before.

How were creators to respond to this new status quo? It goes without saying that the majority were content to glory in it, producing a stream of bombastic tales of good versus evil newly injected with soapy personal drama (following the model of Chris Claremont’s X-Men run) and a dash of ultraviolence (borrowed from Frank Miller’s work but stripped of its thematic resonance). Others reacted against their niche genre’s newfound popularity by pushing it into even weirder corners, seeing just how far the concept could be stretched. I’m thinking of Grant Morrison’s oddball Seaguy, Matt Wagner’s ultra-noir Sandman Mystery Theatre, and Kurt Busiek’s idealistic Astro City, among others. Warren Ellis’ Planetary is something else entirely. It’s a wrecking ball, an outright rejection of the superhero archetype—and, consequently, among the first works that can be called ‘anti-superhero’… or perhaps ‘post-superhero.’

A significant player in the so-called ‘British Invasion’ of comics in the eighties and nineties, Ellis started out at Marvel before hitting it big with Stormwatch and The Authority for the creative-owned studio Wildstorm. Playing with relatively new characters instead of the iconic Marvel and DC stalwarts allowed him to exaggerate, distort, and even render grotesque the familiar myth of the costumed do-gooder. Ellis’ ‘heroes’ waded in vast property damage, upheld shady geopolitical interests over innocent lives, and only looked like the ‘good guys’ when compared to their ridiculously depraved, atrocity-prone adversaries.

Of course, the seminal Watchmen had played the same game a decade earlier (and more artfully, too), but The Authority outpaced it in sheer cynicism. While Moore’s comic still allowed for hope through principled heroes like Nite Owl and Silk Spectre, Ellis had seemingly lost all faith in the validity of superheroes as a character type. The Authority was a reflection of a morally bankrupt American society, victorious in the Cold War but still critically wounded by past traumas. The mindless violence and nihilistic mindset of nineties superheroes, which Ellis amped up to eleven with satirical intent, represented the next stage after the disillusionment of the ‘70s and ‘80s: a world embracing its lack of moral authority and revelling in uninhibited transgression.

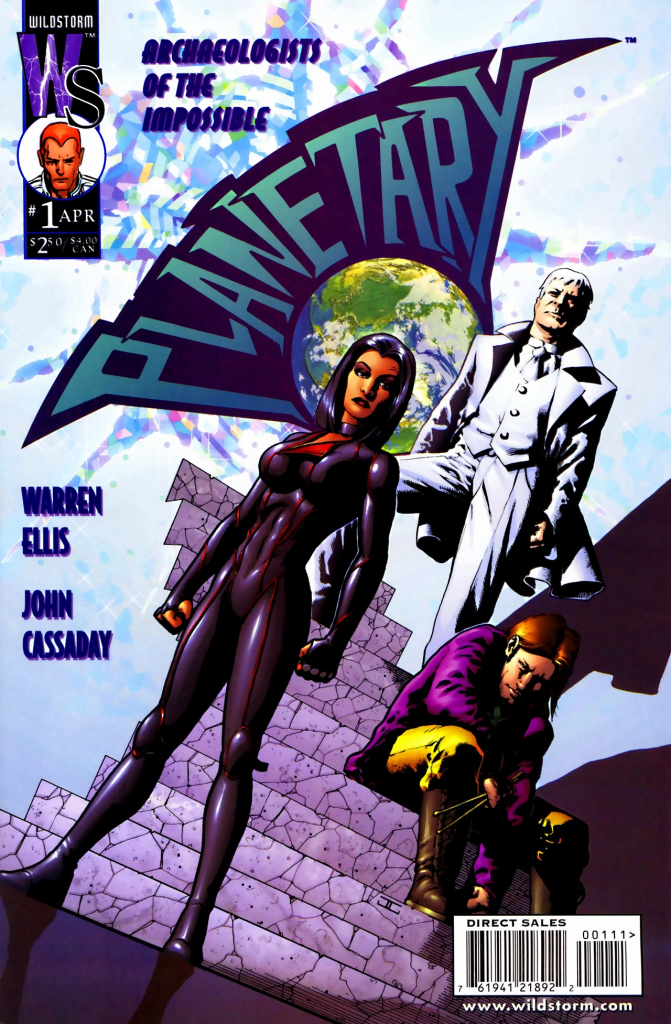

Despite how illustrative The Authority is in revealing the excesses of this period, it’s Planetary that best encapsulates the growing rejection of the superhero as a worthwhile concept by a new generation of writers. This is simply because, unlike its Wildstorm predecessor, Planetary barely features characters that could be called ‘superheroes’. Its first issue introduces us to the Planetary trio: Elijah Snow, a seemingly ageless man with ice powers and the viewpoint character; Jakita Wagner, their leader, who is super-strong and invulnerable; and The Drummer (“FIRST NAME, ‘THE,’ LAST NAME, ‘DRUMMER’”), an antisocial Shaggy lookalike who talks to machines. At a glance, they might resemble the archetype of a super-team, but the subversions outnumber the similarities: no one has a secret identity, their outfits lack a symbol or thematic elements, and they never fight crime. Instead, they are “mystery archaeologists,” hired by a faceless “Fourth Man” (“HE COULD BE BILL GATES. HE COULD BE HITLER.”) to document outlandish happenings around the globe.

Consequently, in most stories, the central conflict is resolved without any help whatsoever from the team; in the first, “All Over the World,” they show up sixty years after an extra-dimensional invasion has already been foiled and meet the sole survivor, a stand-in for pulp hero Doc Savage. The series’ setup soon becomes an excuse for visits to various disparate genres: Japanese kaiju horror, Hong Kong action cinema, and British alternative SF. #5, “The Good Doctor,” even breaks from the form of comics entirely by sporadically shifting into prose with accompanying illustrations. Throughout the 27-issue run, the team runs into fantasy supercomputers, alien colossi, space ghosts, and much, much more. The whole seems to owe more to the action pulps, the superhero genre’s granddaddy, than superhero comics themselves—except with ‘40s pseudoscience replaced with then-cutting-edge scientific ideas like the Monster group.

Given all these departures, Planetary might almost not qualify as a superhero tale at all, or even a subversive one, if not for its overarching villains: thinly-veiled counterparts of the Fantastic Four. Cleverly tying them to Project Paperclip and the unsavoury origins of the American space program, Ellis makes these defining superhero icons into dysfunctional, megalomaniacal caricatures. The superhero concept, Planetary seems to be arguing, is not only obsolete but actively harmful. It represents everything bad about American foreign policy in the chaotic present and the shameful past alike. Like Watchmen, Planetary shows the ugly undercurrents simmering beneath the Golden Age, but that one at least had Hooded Justice intervene to stop the Comedian sexually assaulting Silk Spectre; here, anyone who’s superhero-coded or associated with ‘the establishment’ is by default irredeemable.

How one feels about this approach depends greatly on one’s taste for Ellis’ open-ended, often self-congratulatory writing style. Issue #2, in which the protagonists again do absolutely nothing to resolve the main conflict, ends with a rather random life-affirming twist, to which Jakita observes: “ISN’T THAT GREAT?” There are passages of great beauty, too, like an Atom Age ghost’s poignant demise, but a bad taste lingers—it might have something to do with Ellis’ since-uncovered sexual coercion allegations. Or maybe it’s this: the fundamental paradox of Planetary (like many post-superhero works that would follow) is that it pulls out all the stops to critique superheroes and the system that spawned them yet fails to aim that critical eye at its own heroes, who may be flawed but are inevitably always enlightened and in the right. Ellis’ own Transmetropolitan, Garth Ennis’ The Boys (now a successful TV series on Amazon), and Mark Millar’s Kick-Ass all suffer from this issue to some degree. It’s not insurmountable, but it does cast some doubt on their collective declaration of the superhero’s demise.

In fact, as you may have gathered, serious comics treatment of superheroes didn’t die with the turn of the century at all. As the X-Men, Dark Knight, and eventually MCU franchises sent comic book movies spiralling to greater heights than ever, the comics themselves resisted sinking to the lowest common denominator to pick up stray movie fans. Instead, the 2000s and 2010s saw a fulfilment of Denny O’Neil’s dream of a literary, intelligent treatment of the concept that still respected its roots. Writers like Jeff Lemire, Jonathan Hickman, Mark Waid, Darwyn Cooke, and the everpresent Grant Morrison managed to balance popular success and thematic resonance just like the old masters of the form: Siegel, Shuster, Lee, and Kirby. The superhero, it seems, was more resilient than writers like Ellis gave it credit for. After all, it has survived almost sixty years of rapid change and upheaval already—and its soon-to-come next incarnation is already on the horizon.

Next time: Dawn of X and the next rebirth!