Final part of a new series exploring comics history from the 1930s to the present by considering crucial works from each period. Whether a comic-shop virgin or an obsessive collector, you’re sure to learn something new and surprising!

Four years ago, if you had to bet on the creator who’d bring about the superhero’s long-awaited next evolution, Jonathan Hickman would have been an excellent choice. Some might even argue he had done it already with his seminal runs on Avengers and Fantastic Four. Few writers can match the grandiose vision Hickman brings to each of his projects, echoing Jack Kirby’s cosmic epic style of storytelling; in his hands, the superhero—already by necessity larger than life—takes on an almost godlike stature. In House of X #1, the starting point of his foray into the one major Marvel super-team he’d yet to revolutionize, he goes and takes out the ‘almost.’ As Earth’s ambassadors quibble about the terms of mutantkind’s new covenant with humankind, Magneto silences them with a pronouncement that encapsulates the entire series’ ethos: “YOU HAVE NEW GODS NOW.”

House of X is ludicrously ambitious, but fortunately, it has the creativity and solid worldbuilding to back up its big swings. Such virtues were sorely needed. The X-Men, once by far Marvel’s most popular property, had, at the time of the relaunch in 2018, been suffering at the hands of editorial for some time. Many suspect that the constant calamities (in and out of universe) suffered by the poor cohort of mutants throughout the 2010s, from near-extinction to internal schism to ill-advised time travel plots, were due to a policy of deprioritizing comics characters that Marvel did not own the film rights to. Concurrent attempts to hype up the Inhumans as their replacements didn’t go over too well, either.

It’s important to note that such policies have hardly waned since then. With the spectacular rise of the MCU, the most profitable entertainment franchise of all time, Marvel comics have become increasingly subordinate to their far more lucrative cinematic spawn. In fact, it’s begun to seem as if the Big Two now regard their comics merely as ancillary products to be mined for storylines and pushed on the more diehard movie fans. Fortunately for the X-Men, Disney bought Fox outright in 2019 and brought (almost) all its characters back under a single licensing umbrella, once again giving Marvel a vested interest in their larger success. The time for the mutants’ return to prominence in their native medium had come.

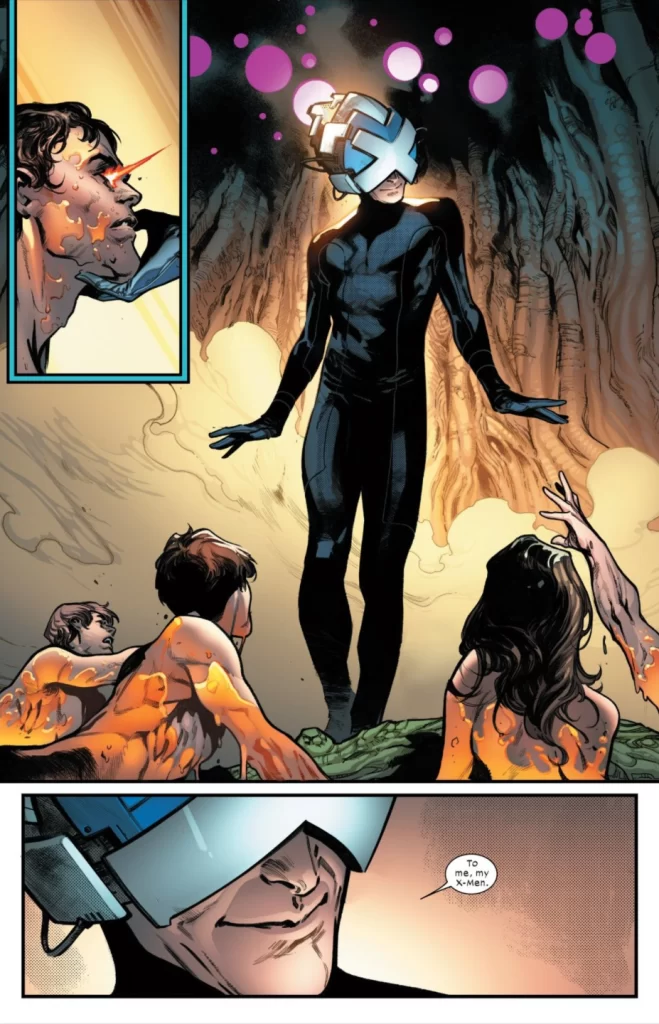

No one was quite ready for what followed. The opening panels of House of X #1 are terrifyingly, unapologetically mythical. We see an enormous bioluminescent tree with a small figure beneath it—Professor X as we’ve never seen him before. The X-Men crawl out, naked and covered in slime, from strange organic-looking pods at the structure’s base. They’re greeted by their leader, who smiles and says ominously, “TO ME, MY X-MEN.” Instead of coming off like a standard catchphrase, the setting and letterer Clayton Cowles’ lower-case work gives the utterance an entirely different connotation. Simply put, it’s spooky. The epigram that sets the scene, “WHILE YOU SLEPT, THE WORLD CHANGED,” says it all. Something is distinctly off here—and it only gets more so as the series progresses.

We soon discover that the X-Men have abandoned their goal of fostering harmony between mutants and humans (only the crux of their narrative since their creation) and have chosen to live on Krakoa, a previously antagonistic living island that now serves as a newly minted nation-state for Homo superior. And yes, that means all mutants—in the interests of unity, Professor X even extends an amnesty to longtime foes like Magneto and Apocalypse. To secure recognition and avoid retaliation from human governments, they provide humankind with miracle drugs that revolutionize medicine, though surprisingly little is made of that plot point. Krakoa, we learn later on, also has the ability to bring its denizens back from the dead, ‘downloading’ the latest version of their minds onto newly manufactured bodies. In short, Hickman is shattering the very basis of the classical superhero conflict here—not only are the heroes and villains no longer at odds, but both now have unlimited lives (finally making superheroes’ notorious propensity for resurrection outright canon) and are no longer interested in saving or harming humans. So what now?

Fortunately, House of X has multiple, equally compelling answers to that question. The six-issue miniseries, cleverly intertwined with Powers of X (also by Hickman), tells an expansive SF story across four different timelines that sets up the new status quo with elegance and nuance. There are dozens of little threads, from long-dead mutants resurrected to jurisdictional clashes with other heroes to a classic character’s unexpected (and canon-shifting) mutant power, rife for exploration in other titles. And indeed, the Krakoa sandbox created by Hickman has already proved its capacity to host a wide variety of stories as it expands to magical realms, future timelines, and even a sub-dimension populated entirely by mutants. It’s that rarest of things in modern comics: a radical reset for a whole family of titles that isn’t wiped away in favour of the familiar within a year or two.

That success should be a lesson for an industry far too obsessed with playing it safe and tying into familiar versions of well-known characters (and their film counterparts). DC isn’t blameless here either, as evidenced by their endless slew of increasingly confusingly named Batman titles. Across this very series, we’ve seen how the biggest leaps in the evolution of the superhero archetype have come through radical departures from audience expectations rather than playing it safe. Look at how Lee and Kirby subverted the Golden Age ideal with the painfully human Fantastic Four or how O’Neil radically transformed the Question’s original character to create a hero more suited to an age of uncertainty and doubt. Even Superman himself, stripped of the softening filter of nostalgia, seems like a daring metamorphosis of the pulp hero into something almost non-human. And, contrary to the view of writers like Ellis in the ‘90s, that same model remains very much relevant—but in order to remain as such, it must continue to change with the times.

Hickman envisions the X-Men as post-human in the truest sense; their story transcends time, conventional morality, and even death. In his hands, what might have been a generic event book becomes a grand experiment in the outer limits of the form. How far into the wild realm of science fantasy can we go and remain within the confines of superhero fiction? That exploration is thrilling to witness—and entirely impossible within the normal editorial restrictions of mainstream comics. It’s past time the industry began allowing genuine changes to characters dating from over fifty years ago, to let the full promise of the new era House of X presages play out. It may not yet be apparent what that entails—we’re just on the cusp of it so far—but the time is ripe for this new dawn. As Magneto declares to Xavier toward the end of House of X #6, “JUST LOOK AT WHAT WE HAVE MADE.” Hickman has indeed made a historic step; now, it falls to others to go even further. Looking back on all this bold, risk-taking history we’ve covered, I get a feeling they will.

Thank you for reading! See you at the newsstand, true believers…